CONTINUED FROM MODULE 2 PART 4

COMING TO AMERICA

How, then, did Gojira become Godzilla? In order to understand yet another one of Godzilla’s beginnings, it’s necessary to follow him across the Pacific to the United States, one of the earliest stops in what would become a worldwide journey.

If observers from a distant planet were to judge by the output of Hollywood studios, they might well conclude that monsters ran rampant in early Cold War America. An unprecedented sci-fi and horror boom visited U.S. cinema during the Fifties, and showed few signs of fading until the middle of the next decade. For many fans, the heyday of what later became known in the American vernacular as the “creature feature” remains one of the hallmarks of that earlier, more innocent era. Although scholars have arrived at various interpretations of this cultural phenomenon, most would agree that part of the explanation rests with the peculiar geopolitical conditions of the Cold War. For one thing, as with many aspects of American popular culture during the Fifties, the various stories of alien invasion that unfolded on movie screens across the nation resonated in subtle yet potent ways with widespread popular anxieties about external threats to national security. No doubt the fact that the invisibility of the enemy lies in the very nature of “cold” warfare made such visible phantoms all the more alluring. Similarly, monstrous mutation might offer an apt metaphor for the supposed dangers of communist subversion from within, a concern that found its most extreme expression in the McCarthy hearings. At the box office, as on Capitol Hill, paranoia pays.

To be sure, not many Americans went to the movies for consciously ideological reasons. Nevertheless, cultural artifacts, including (or perhaps especially) popular films, do not operate in a cultural vacuum. Rather, as the philosopher and critic Frederic Jameson has argued, they interact with the prevailing social tensions of their time, or what he calls the “political unconscious.” Think about that the next time you watch I Married a Monster from Outer Space.

It goes without saying that monster flicks were also fun. The creature-on-the-loose formula never failed to draw gasps and screams from movie audiences, whether in the U.S. or elsewhere. And yet people came back for more, as the sheer number of such films made demonstrates. To satisfy the demand for visual thrills, and to line its pockets in the process, the American film industry cranked out B-movie after B-movie, creature after creature. At the same time, because making a film was a laborious, expensive, and risky undertaking, entrepreneurs in Hollywood searched far and wide for finished products that could be retailored, at a lesser cost, for the domestic market. That’s where Godzilla came into the picture.

By the end of 1955, a year after Gojira‘s Japanese release, at least one ethnic movie house in Los Angeles had played the original in its full and uncut Japanese-language version. But most people in the U.S. likely didn’t know that such specialty theaters existed. Nor would mainstream Americans be inclined to watch a foreign-language film even if it had subtitles—that was for the art-house crowd. One available option for naturalizing foreign movies was to dub the voices into English. Yet at the end of the day, a different strategy was chosen for bringing Gojira in line with American tastes. One of various challenges faced by Gojira‘s U.S. promoters was the fact the film embodied certain perspectives and contained certain lines of dialogue that, if rendered into English with uncompromising accuracy, some Americans might find difficult to understand, unpleasant, or possibly offensive. Of particular sensitivity in a nation that supposedly led the Free World were the film’s critical references to U.S. foreign and military policy, both explicit and implicit, historical as well as contemporary.

The solution that emerged was the brainchild of two small-time Hollywood producers named Richard Kay and Harry Rybnick. Their production outfit, Jewell Enterprises, purchased the U.S. and Canadian rights to the film in late 1955 from an American distributor by the name of Edmund Goldman. Goldman, who ran a company called Manson International, had earlier acquired those rights for the sum of $25,000 from “International Toho, Inc.,” a small overseas office that the Japanese studio maintained in Los Angeles. In contrast to Goldman, Kay and Rybnick were determined to go the whole way with their investment. They recognized that the original film, while visually impressive, would require substantial reworking in order to appeal to American audiences, and, furthermore, they possessed the necessary contacts to carry out the transformation.

Kay and Rybnick immediately set about raising further capital in order to retool the Japanese movie as well as to generate large-scale publicity for an independent picture that lacked the backing of a major Hollywood studio. A $100,000 infusion came from the rising film impresario Joseph E. Levine (1905–1987), whose Embassy Pictures was based in Boston, and who brought in additional partners such as Terry Turner and Edward Barison. At the same time, Kay and Rybnick chose veteran editor-director Terry Morse (1906–1984) to rewrite the story along with professional screenwriter Al C. Ward (1919–2009), and to direct the new segments as well as combine them with the original. Finally, it was Kay and Rybnick who decided to hire Raymond Burr (1917–1993), an up-and-coming Hollywood actor, Canadian by birth, to appear in the reedited feature. By doing so, they would be able to put a familiar Anglo-Saxon name, instead of a multitude of unknown Japanese ones, on marquees and billboards across the nation. The picture that resulted received the title Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, complete with a sensationalizing exclamation point. Interestingly, the creature’s English name already appeared as Godzilla (rather than as Gojira) on Goldman’s original contract with Tōhō, a fact that suggests the anglicization came directly from studio offices in Tokyo and was not an American creation. So as to avoid confusion, this website refers to the 1954 Japanese film as Gojira and to the 1956 Hollywood retailoring as King of the Monsters.

Different accounts have Raymond Burr spending between one and five days filming his part of King of the Monsters. English dubbing of the Japanese dialogue is said to have been accomplished in the space of a day. All told, the resulting feature mixed newly written scenes with existing ones in a fairly original and effective way. The plot device that allowed this hybrid to take shape was to cast Burr as an American foreign correspondent, Steve Martin, and to edit Martin’s presence into the original story as an eyewitness to its main events in quasi-documentary style. The audience hears Martin’s voice as a first-person narrator, and sees him attending press gatherings, participating in an expedition to Ōdo Island (we’re assured that he’s been “cleared by the Security Office”), speaking with the main characters (or rather with identically dressed body doubles), and observing Godzilla’s destruction of Tokyo through a pair of binoculars. He even receives a nasty blow to the head from a falling beam in his news office, and undergoes treatment at a makeshift hospital—where, as film fate would have it, he runs into Dr. Yamane’s daughter Emiko, Gojira‘s lead female character. A surprising amount of Japanese-language dialogue remains in King of the Monsters, with Martin often asking his inexplicably bilingual Japanese sidekick, security officer Iwanaga, to translate what the locals are saying. His own Japanese, Martin claims, is “rusty,” although he can manage an occasional sayonara.

Although Terry Morse and his crew added new footage to the original, they also took a fair amount away and rearranged much of what remained. The final version of King of the Monsters clocks in at 80 minutes. Since 1954’s Gojira ran 98 minutes, only 58 minutes of which Morse retained, it goes without saying that the two movies diverge in significant ways. In general, the differences fall into one of two categories. The first are fundamental modifications to the plot, which serve collectively to put Steve Martin at the center of the action while taking away some of the corresponding emphasis from the romantic triangle that had structured the Japanese original. The melodrama of the story revolved around the premise that Emiko, although engaged to her father’s young scientist associate, Dr. Serizawa, has fallen in love with Serizawa’s friend Ogata, a junior employee at a ship-salvaging company. (King of the Monsters describes Ogata, somewhat confusingly, as a “marine officer.”) By portraying Emiko and Ogata’s romantic liaison in a positive light, and by literally sacrificing Dr. Serizawa in the end, Gojira, like many popular Japanese films of the postwar period, presented “love marriage” as a cultural ideal. Affectionate but by no means ardent matches like the one depicted between Emiko and Ogata, who’s purportedly a longtime friend of the family, came to appear less attractive under the increasingly fashionable ideology of romantic individualism. Indeed, Japan’s postwar Constitution, promulgated in 1947, specifically guaranteed the right of men and women to choose their own spouses. For Americans, on the other hand, who were not well informed about these cultural debates and had a different set of courting practices, the melodramatic elements of the plot may have been less compelling, and could be substantially trimmed without losing much in the way of audience interest.

The other important area of difference involves the two films’ political overtones. Since American nuclear testing was part of Godzilla’s background not only in the original script but in real life (most specifically, the Lucky Dragon incident of March 1954), a certain amount of finesse was required to reconcile Gojira‘s implicit challenge to U.S. nuclear policy with the ideological sensibilities and national allegiances of its new target audience. Indeed, Gojira even contains a scene, suppressed in the Hollywood version, in which a Japanese politician argues, rather tellingly, that the monster’s atomic origins ought to be concealed because to publicize them might lead to serious “international problems.” America’s name is not specifically mentioned, but American sensitivities are clearly implied.

It’s hardly the case, though, that King of the Monsters is Gojira stripped of its antinuclear content. Fear of the Bomb was a moneymaker rather than a taboo in Fifties Hollywood, and even if one had wanted to do so, it would have been difficult to rinse out Godzilla’s radioactive roots entirely. There was enough atomic anxiety in King of the Monsters to go around. Even so, when faced with Gojira‘s repeated references to past and present nuclear issues, some of which raised the specter of “international problems,” the film’s American retrofitters felt the need for certain changes, whether consciously or unconsciously, and for reasons that involved not only politics but also commercial and stylistic considerations. It’s necessary to evaluate those choices in a broader geopolitical, historic, and cinematic context.

More problematic than the fact that Gojira offered an antinuclear critique per se was the fact that this critique originated from a movie industry not in Hollywood but in a foreign country, and in a former enemy state at that. More than a decade’s worth of geopolitical and historical circumstances had shaped the course of Gojira‘s transformation into King of the Monsters. Any implication that U.S. stewardship over the Free World was anything but wise or fair would have been anathema, which is to say bad business, in Fifties Hollywood, the epicenter of the nation’s culture industry. By 1956, Japan had become the primary bastion of American military, political, and economic interests in East Asia, a region of the world where Cold War had only recently turned hot in Korea and where a Bamboo Curtain now hung alongside its Iron predecessor. The country of Godzilla’s birth had undergone a remarkable metamorphosis from wartime enemy to strategic ally of the U.S., including an extended period of territorial occupation meant as an apprenticeship in capitalist democracy. The relationship of teacher and student, of protector and protected, replicated itself visually in King of the Monsters through Raymond Burr’s towering physique—reminiscent of the famous post-surrender photo of General MacArthur standing next to a tiny Emperor Hirohito—as well as in his character’s friendly yet ever so slightly patronizing air toward the Japanese with whom he interacts. Burr’s presence may have helped reassure some American viewers that their nation’s influence around the world remained powerful and that Uncle Sam always kept his eye open for untoward developments. Indeed, as exemplified by the Alfred Hitchcock classic Foreign Correspondent (1940), Martin’s profession was one that American popular culture already associated with foreign intrigue and the protection of national interests.

The divergent endings of the two Godzilla films also reflected the two nations’ asymmetrical positions on the Cold War gameboard—the one a cautious follower of a superpower, the other a self-appointed and largely self-satisfied leader. The last line of Gojira contained an obvious, though not necessarily belligerent, challenge to U.S. authorities. Dr. Yamane, the wise and humane patriarch, warns solemnly that, “If we keep conducting nuclear tests, another Godzilla might again appear somewhere in the world.” In contrast, the conclusion of King of the Monsters is upbeat and reassuring, with Steve Martin commenting after Godzilla’s demise: “The menace was gone…. [T]he whole world could wake up and live again.” As was frequently the case with Hollywood sci-fi in the Fifties, people in the audience might breathe a sigh of relief that the alien threat had been beaten back and that the Free World could continue going about its business in peace, confident of its future and secure in its defenses. A few may have recalled a scene at the beginning of the movie in which Steve Martin, narrating retrospectively from the future, claims that downtown Tokyo, ravaged by Godzilla, will eventually return to the pristine state that appears onscreen in a stock aerial shot. It’s fitting that Burr, with his soothing voice and confident air, would shortly come to personify Cold War America’s establishment values again in the popular TV drama Perry Mason (1957–1966). And it must have been comforting for Americans in 1956 to be assured that even a city “devastated as if by atom bomb”—as one reviewer put it—could bounce back to capitalist prosperity.

Figure 2-12-001

For Gojira‘s original audience in 1954 Japan, the Pacific War was a recent, and in many ways still living, memory. Human lives and limbs remained visibly scarred, along with the physical landscape of the country. This historical context, though painfully evident at the time, is all too easy to forget more than half a century later, especially in America, which hasn’t seen all-out warfare on its national soil since the Civil War era.

The scars of war, and particularly of the Pacific War, indelibly mark the film Gojira. They are visible, for instance, in the character of Dr. Serizawa, who mounts the staircase in a dramatically posed U.S. lobby card (Fig. 2-12-001) for King of the Monsters. In postwar Japan, ex-soldiers with eyepatches or other signs of wartime injury were a fairly common sight, so audiences in that country probably needed little prompting to intuit the character’s military background. The skin below Serizawa’s patch is also scarred, although, unlike the eyepatch, it’s not terribly obvious in the photograph, or for that matter in currently circulating prints of the film itself. Japanese publicity posters for Gojira show the scar much more clearly.

Whether in Japan or America, cinemagoers were also likely to relate Serizawa’s striking appearance with the stereotype of the “mad doctor,” which literary and cinematic tradition had long associated with bodily disfigurement. In the original story treatment by KAYAMA Shigeru, that same tradition had already helped mold another of Gojira‘s scientist characters, Dr. Yamane. Like many Japanese mystery and fantasy authors of the postwar period, Kayama found inspiration in the prewar writings of his countryman EDOGAWA Ranpo (1894–1965)—whose pen name was intentionally, if imperfectly, homophonous with the American master of horror, Edgar Allan Poe—and other sources of the mad-scientist lineage. Subsequently, Honda’s and MURATA Takeo’s screenplay for Gojira transferred some of Dr. Yamane’s classic eccentricity onto the figure of Dr. Serizawa. In the final version of the film, Serizawa lives in a large and gloomy Western-style mansion, where he listens to classical music and spends long hours in a downstairs laboratory full of bubbling beakers and all manner of mysterious devices.

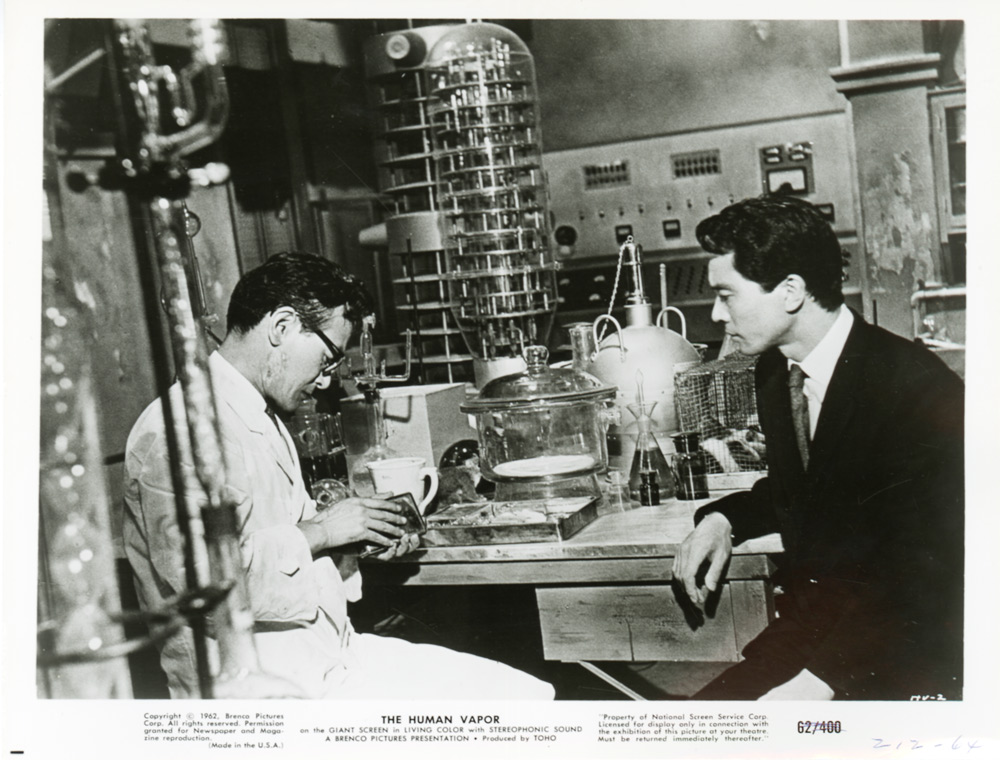

Figure 2-12-002

We encounter yet another reincarnation of Serizawa’s “mad doctor” in The Human Vapor, a somewhat less celebrated 1960 collaboration by Honda, Tanaka, and Tsuburaya. As a U.S. publicity still (Fig. 2-12-002) reflects, that film’s morally challenged scientist, Dr. Sano (at left), works in a similarly equipped laboratory, a veritable man-cave of Gothic gloom and gurgling glassware. His right cheek bears a made-up scar that’s a bit easier to make out than that of Gojira‘s Dr. Serizawa. The screenplay gives no explanation for Sano’s disfigurement, but viewers of a certain generation in Japan could have assumed a wartime origin.

The facial scars and other signs of war-related suffering that kaijū/tokusatsu films feature, if only occasionally, are mild in comparison to the imagery that people today commonly associate with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The reason has to do, at least in part, with genre, since film horror frequently distills human anguish into the figure of the monster, rather than focusing on the horrific doings of ordinary people. Among other genres of film, dramas and documentaries may tend to keep the story at a human level, but they, too, operate within historical and generic constraints on what can and can’t be represented. Some of the most controversial examples of visual censorship in America have involved issues of war responsibility and nuclear guilt, as the 1994 Enola Gay flap at the Smithsonian Institution served to demonstrate even long after the Pacific War ended.

Between 1945 and 1952, American censors poured considerable effort into preventing the Japanese public from reading detailed accounts or seeing graphic images of the atomic destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Their fear was evidently that such knowledge might foment anti-U.S. sentiment among the occupied population. Word of mouth spread far and wide, but only a minority of Japanese had seen the Bomb’s immediate aftermath in person. One exception was Gojira director HONDA Ishirō, whose train passed through Hiroshima in early 1946 on his way back from internment in China. It wasn’t until after 1952, when the Occupation was lifted, that Japanese filmmakers could express themselves more openly—albeit, within the context of an ongoing U.S.-Japanese security alliance, never with perfect freedom—about the scale of the atrocity.

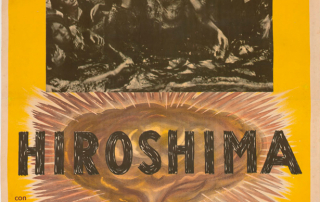

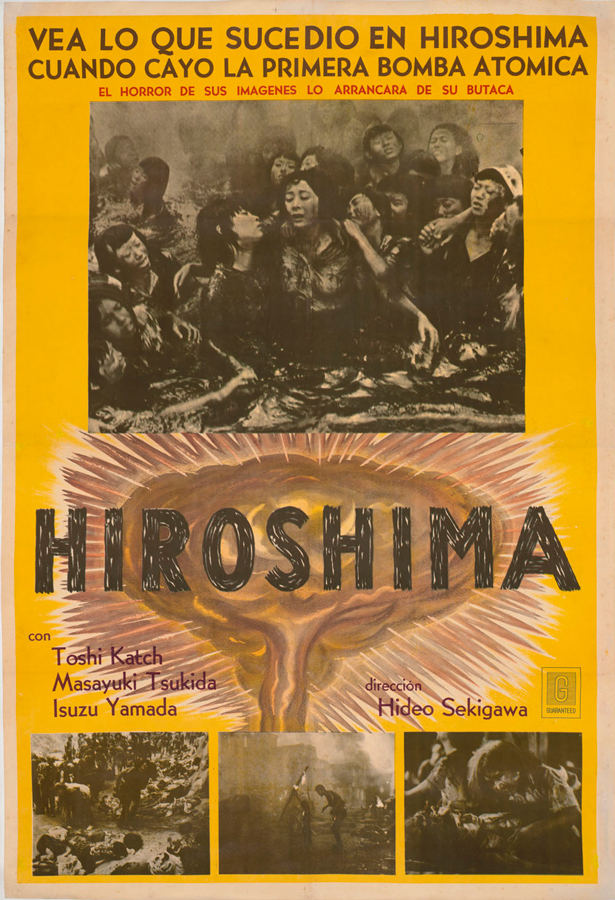

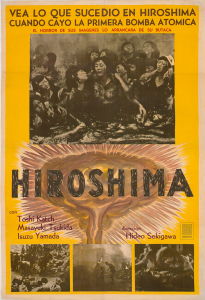

Within a year or two of the Occupation’s end, Japanese directors SHINDŌ Kaneto, who was a native of Hiroshima, and SEKIGAWA Hideo (1908–1977) had both released films highlighting the suffering that the people of the two A-bombed cities underwent. Shindō’s Children of Hiroshima (J. title: Genbaku no ko; 1952) and Sekigawa’s Hiroshima (1953) both took the form of dramas, but they also included a fair amount of documentary footage. The films circulated abroad as well, where many millions were anxious to “see what happened in Hiroshima when the first atomic bomb fell,” as the Argentinean poster (Fig. 2-12-003) for Sekigawa’s Hiroshima put it. Although the 1955 U.S. one-sheet poster (Fig. 2-12-004) for Hiroshima was visually more subdued than its South American counterpart—no mushroom cloud, for example—it was also a bit more irreverent, promising viewers a “blast” they could walk away from, much like a contemporary exploitation feature. Contrastingly, one industry commentator in India rued the local distribution of Sekigawa’s film for ideological reasons, explicitly calling it “Commie product” (1957 Film Daily Yearbook of Motion Pictures). Among Hiroshima‘s backers was the national union of Japanese schoolteachers, Nikkyōso, which was a frequent target of rightist criticism inside Japan as well.

Films dealing with Hiroshima and Nagasaki found particular favor inside East Bloc countries. From a Kremlin perspective, their political value derived above all from the fact that it was the United States, the current Cold War enemy, that had originally developed and had actually deployed the Bomb, ostensibly signaling the moral bankruptcy of the capitalist system and justifying Soviet possession of “defensive” nuclear weapons. Interestingly, it was Shindō’s Children of Hiroshima rather than Sekigawa’s “Commie” Hiroshima that seems to have played more widely in Iron Curtain countries. Ironically, the left-leaning union Nikkyōso had initially considered sponsoring Shindō’s Children of Hiroshima, but in the end withdrew its support to back Sekigawa’s more doctrinaire Hiroshima project. (Both films derived inspiration from the same 1951 collection of children’s essays, just as both featured a score by IFUKUBE Akira, who would recycle parts of Hiroshima‘s theme music in 1954’s Gojira.) Children of Hiroshima reached cinemas in East Germany and Poland, as well as circulating in Tito’s Yugoslavia. Sekigawa’s Hiroshima did, however, play in communist Romania.

In the Polish publicity poster (Fig. 2-12-005) for Children of Hiroshima, artist Jan Lenica (1928–2000) adopts a universalizing approach to the theme of urban devastation: no mushroom cloud, no conspicuously Japanese details. By contrast, Lenica’s Yugoslavian counterpart (Fig. 2-12-006) emphasizes the film’s Japanese origins by orientalizing the lettering of the title, which can be translated as “Atomic Bomb over Hiroshima,” as well as by foregrounding the face of lead actress OTOWA Nobuko (who would later become director Shindō’s wife). The East German poster (Fig. 2-12-007) for Children of Hiroshima, featuring a kimonoed and aerially targeted mother and child, acknowledges the Japanese historical setting of the atrocity unmistakably even as the silhouette of an American Superfortress bomber reminds Communist German viewers of the continuing threat of U.S. military airpower in the context of an escalating Cold War and a divided Germany.

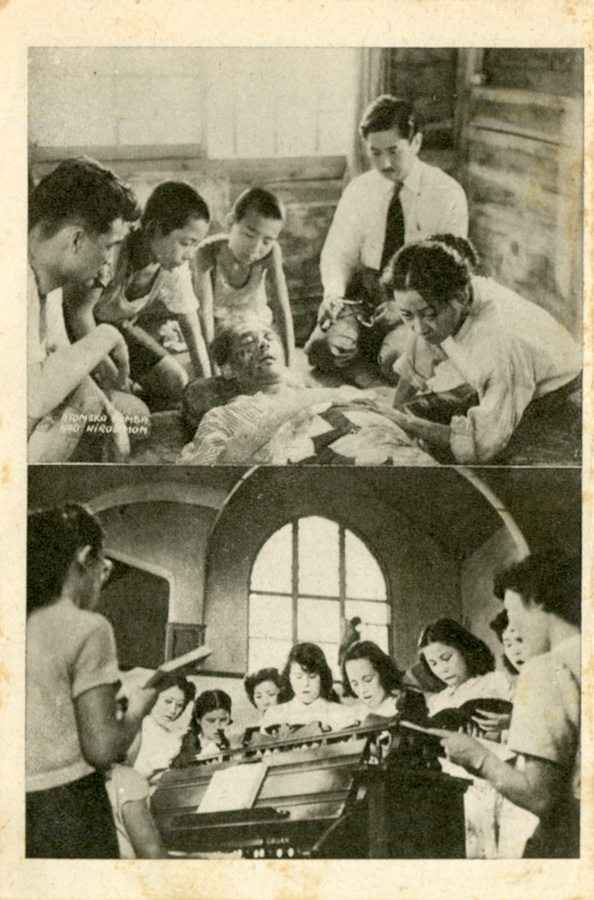

Back in Japan, Children of Hiroshima also made a visible impression on the makers of Gojira. For example, in one of Gojira‘s key scenes, a chorus of schoolgirls gathers in a large auditorium to offer a hymn of peace, supposedly broadcast nationwide over radio and television. Its emotional impact convinces the tormented Dr. Serizawa to sacrifice himself and his ultimate weapon of mass destruction for the sake of human survival. That moment echoes a memorable episode in Children of Hiroshima, made two years earlier, in which a group of young females in school uniforms stand solemnly around a piano in the hall of a church or orphanage, lifting maidenly voices in a song of prayer. A photograph of the earlier scene appears on the back cover of a Yugoslavian program (Fig. 2-12-008) for Children of Hiroshima. Featured directly above it is a shot of a family gathered by the sickbed of a radiation victim, another visual trope that Gojira‘s cinematography recycles.

But there’s also another historical aspect to consider. When it comes to U.S.-Japan relations, past enmities complicated the geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War present. It wasn’t contemporary tensions so much as the lingering wounds of the earlier Pacific conflict [VISUAL SIDEBAR 12: Scars of War], which had put Japan and the U.S. at odds with each other, that accounted for some of King of the Monsters‘ most conspicuous omissions and silences. Because Japan and the U.S. were key allies within a current-day political context, the mention of past hostilities brought up sensitive issues, both on a political and a personal level. Most of Gojira‘s initial Japanese audience had seen war firsthand. For them, visual and auditory allusions were enough to evoke vivid memories of that traumatic period: air-raid sirens, raging firestorms, urban evacuations, searchlights in the night, blackouts, stretchers, people huddling in shelters, smoldering remains of buildings, and so forth. It’s not that Americans couldn’t recognize such signs of war and suffering, but rather that most had not experienced them on their home turf—which is to say, just outside the cinema’s doors. That historical difference between the two countries made it necessary for Raymond Burr to supplement the visual horror with verbal narration, delivering such ponderous lines as “[I]t turned out to be a visit to the living hell of another world.” At the same time, the fact that this sort of wartime experience was indeed “another world” for most Americans tended to shield the audience from its historically specific implications and made it easier to screen out potentially unsettling reminders.

What Japanese needed little reminding of was that, even before Hiroshima or Nagasaki, hundreds of thousands of ordinary civilians had died, been injured, or been left homeless as a result of American firebombing. Tokyo was the hardest hit of Japanese cities, napalm raining down on it from B-29s that flew in over Tokyo Bay almost nightly after Allied forces captured Micronesia’s Mariana Islands late in the war. It’s no coincidence, as historian TANAKA Yuki has pointed out, that Godzilla does his greatest damage to Tokyo at night and that he approaches the city from the same southerly direction. Past and present similarly converge in a scene of Gojira where a woman with two children huddles helplessly on a sidewalk, her eyes gazing upward, as Godzilla devastates the Ginza area. “We’re going to be with daddy soon,” she tells her son and daughter in preparation for their impending annihilation. More than a few members of the Japanese audience would have assumed that the woman was one of the country’s many war widows, and surmised that her husband had departed heavenward while fighting Allied forces in the Pacific or on the Asian continent. The scene remains intact in King of the Monsters, but Morse and Ward, tellingly, chose to leave the dialogue untranslated. Nor would most Americans have been able to make out, much less understand, the character’s faint words in the background. As a result, the woman becomes an ahistorical and anonymous figure, the poignant expressions on her face doing little more than to reflect the generic terror that giant monsters create.

In addition to resuscitating the spectacle of urban firebombing, Gojira makes a variety of visual and verbal allusions to the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Audiences in Japan were even more likely than their American counterparts to think of one if not both these cities when faced with the sight of disaster victims plus doctors with Geiger counters. While the global danger of nuclear holocaust was a topic that explicitly or implicitly motivated many U.S. films of the Fifties, it was less than comfortable for American viewers to contemplate the fact that the only use of atomic weaponry in actual warfare had been by their own country, and that it was directed, ironically, at a current ally. In addition, many U.S. veterans of the war, and a good portion of the general public, would probably not have swallowed with ease any reference to the bombings by a Japanese filmmaker, particularly if it assumed moral or critical overtones. They might not even accord him or her the respect of the last two syllables.

King of the Monsters scriptwriters Morse and Ward were surely aware of such sensitivities, and they may therefore have felt justified in cutting one of Gojira‘s most crucial scenes. Shortly before witnessing Godzilla’s attack on Tokyo, audiences in Japan were shown the crowded compartment of a commuter train carrying three office workers, one of them female and the other two male. The men hold newspapers featuring headlines related to Godzilla, which leads to the following conversation:

The tone of the dialogue is chatty rather than tragic, but the lines help to connect some dots and to draw parallels between past, current, and fictional events. “Irradiated tuna” refers directly to the 1954 Lucky Dragon incident, which for a time led consumers in Japan as well as in the U.S. and some other countries to refrain from buying that popular fish for fear of radioactive contamination.

As the train scene illustrates, the fictional scenario of Gojira reminded Japanese audiences explicitly not only of events in 1954, the year the film debuted, but of the catastrophic war period of the early Forties. That war ended in 1945, days after the Nagasaki explosion. Even the younger male passenger could easily have been evacuated from Tokyo or another large city during the war in order to escape air raids, a practice that sometimes involved relocating entire grades of a school to the countryside. The trio’s commiseration over the remembered difficulties of evacuation underscores the point that Godzilla is an embodiment not just of radioactive danger but also of other kinds of devastating twentieth-century military technology.

Among the combatant nations of World War Two, it was distant and wealthy America that relied most heavily on the new technologies of mass destruction. Not many people outside Japan remember that Allied firebombing of the archipelago killed nearly as many people as the two atomic blasts put together. It’s necessary to note that Japanese forces, too, were guilty of bombing entire cities, especially in China. Yet the fact remains that the use of weapons of mass destruction was more the strong suit of the Allies than of the Axis. Americans in particular have historically favored WMDs, which magnify the horrors of war even as the vast majority of the population, safe thousands of miles away from the conflict, remains screened from their effects. The nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll, some might say, was one episode in a continuing project.

By bringing together Nagasaki and the Bravo Shot (“irradiated tuna”) in the same conversation, Gojira linked the tragic lessons of World War Two with the ongoing Cold War situation. Both conflicts had unleashed terrifying new technologies of destruction at Japan’s doorstep. The ones to suffer, the film implies, are ordinary people like the garrulous office worker on the train, or her countrywoman huddling on the sidewalk—not a surprising choice of gender in either case, given the strong presence of females in the postwar Japanese antinuclear and peace movements. Tellingly, King of the Monsters erases one of these women and silences the other. It also leaves untranslated the voices of protest that a largely female group of Diet members raise when a conservative male colleague suggests covering up Godzilla’s nuclear origins; nor, for that matter, does the audience hear the man’s original proposal. It would be misleading to imply that all these changes arose from a consciously and consistently applied ideological strategy. Other factors, including questions of running time, narrative considerations, language difficulties, genre conventions, and institutional differences, clearly fed into the mix. Still, no one can deny that U.S. audiences never got to see or hear a good deal of the material that stood at the original Gojira‘s political core.

Nevertheless, an atomic monster is an atomic monster. U.S. publicity posters for King of the Monsters defined Godzilla’s radioactive breath only as a “death ray,” but it didn’t take a nuclear scientist to know what was involved when the bodies of victims set Geiger counters chattering like Rice Krispies. Similarly, when Dr. Yamane hypothesizes, in King of the Monsters, that a prehistoric creature has been “resurrected due to the repeated experiments of H-bombs,” few audience members would have been so naïve as to place the blame for the monster’s reawakening on the Soviet Union exclusively. The “strange burns” seen on Godzilla’s victims had been etched into the American subconscious for over a decade, and visual images had an uncanny power to draw that awareness to the surface. In the eyes of one Boston reviewer, King of the Monsters‘ devastated cityscapes “look[ed] suspiciously like actual films taken after the dropping of the atom bombs in Japan.” He or she continued with telling brevity: “They are uncomfortable views.”

No matter how much they had squirmed in their seats, it’s difficult to imagine many Americans of the Fifties signing ban-the-Bomb petitions just because they’d enjoyed the show. And of course the real Ike—unlike the fictitious President Wilson of KAYAMA Shigeru’s original story treatment—would announce no moratorium on nuclear-weapons development. Still, Godzilla, King of the Monsters, planted a deep footprint on the nuclear imagination of Cold War America, and was on his way to becoming one of the most widely recognized and most enduring icons of the Atomic Age. He was more than ready to take on the world.