A KING IS BORN: Godzilla’s Multiple Origins

Gregory M. Pflugfelder

©2015

Like any phenomenon of cultural history, Godzilla has many beginnings. These are some of the most important to know.

For a start, there are the fictional origins of the creature as the first Godzilla film tells them. That film is Gojira, released in Japan in 1954. The name “Gojira”—which in English would eventually be transliterated as Godzilla—is first spoken in the movie by one of the inhabitants of an imaginary place called Ōdo Island (Ōto is also an acceptable pronunciation of the island’s name). There, the film has it, folk belief once held an awesome sea creature by the name of Gojira to be responsible for poor catches and other misfortunes that periodically threaten the livelihood of the island’s humble fisherfolk. In former times, supposedly, Ōdo islanders handed down a tradition of sacrificing a young maiden in order to appease the monster. Custom dictated that they set her afloat on the ocean, presumably never to return.

The film doesn’t make clear exactly when “Ōdo islanders” abandoned this form of sacrifice. But it introduces viewers to another type of ancient religious ritual that undoubtedly survives in the real world. In one of Gojira‘s early scenes, a group of local residents congregate at a Shinto shrine just as a devastating typhoon—accompanied, as it turns out, by the monster Godzilla—approaches the island. There, they offer a kind of sacred dance, accompanied by music played on traditional Japanese instruments. It’s a ritual of supplication and pacification called in Japanese kagura—literally, “entertainment for the gods.”

An origin myth thus lies at the very heart of Gojira. The film’s creators make a conscious (if entirely fictitious) attempt to link the monster with Japan’s historical past and Shinto’s religious worldview. The earliest written records in Japan, which date from the eighth century and are based on oral traditions not unlike those of the fictional Ōdo Island, are full of mythic creatures and of beings that bridge the human and the divine. In Shinto belief, the deities of nature are known as kami, and exert a significant influence over human affairs. Even the movie studio that made Gojira acknowledged their power by celebrating the film’s wrap-up and praying for its commercial success before a miniature Shinto shrine that company workers erected on the lot, topped with an effigy of Godzilla himself (or more accurately speaking, part of his rubber suit). Today as well, Shinto rituals, objects, and sites of worship can easily be found in the midst of an ultramodern urban landscape. It’s in part through Shinto that many people in Japan imagine an enduring connection with their nation’s past and with a simpler, rustic way of life centering on family, community, and an unspoiled natural environment.

The religious tradition called Shinto, which extends back more than a millennium, has acquired only a limited following outside Japan. Nevertheless it has left and continues to leave its imprint on many of that country’s cultural exports, even those that aren’t explicitly religious or spiritual. Monster movies are no exception.

Shinto grounds the human experience of divinity in feelings of awe and reverence. According to Shinto belief, practically any creature or thing can be a deity, or what Japanese call a kami. But natural objects that are large in size or unusual in shape make especially good candidates for kami status. As an eighteenth-century Japanese scholar, MOTOORI Norinaga, put it, the category of kami designates those things that “have exceptional powers and ought to be revered,” including out-of-the-ordinary animals, plants, bodies of water, and mountains, as well as certain special humans, such as the occupants of the imperial throne. Motoori noted that kami comprise “not only mysterious beings that are noble and good but also malignant spirits that are extraordinary and deserve veneration.” Clearly, a sense of wonder and not moral evaluation informs Shinto attitudes toward the phenomena of the universe.

Kaijū movies display similar traits. In the fictional world they bring to life, awfulness lies only a step away from awefulness, and it’s normal, indeed expected, for people to react to monsters with a mixture of fear and reverence. Godzilla offers a prime example, having gotten his legendary start as an object of Shinto worship, as much venerated as dreaded by the inhabitants of Ōdo Island.

Figure 2-01-001

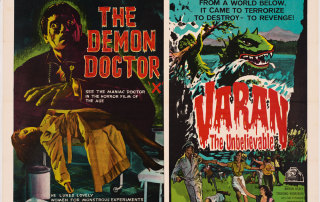

The “kami as kaijū” conceit isn’t unique to Gojira; instead, it imprinted the larger kaijū eiga genre with varying degrees of subtlety. Among the films that most conspicuously recycle the “monster-deity” motif is 1958’s Daikaijū Baran (Giant monster Varan), Tōhō’s fourth venture in kaijū moviemaking. The black-and-white feature introduces audiences to Varan, a giant flying lizard that supposedly makes its home in an isolated mountain lake in the northeastern part of the Japanese archipelago. According to the screenplay, villagers who live in the area revere the creature—subsequently revealed to be a surviving dinosaur—as a “mountain deity” (yama no kami or sanjin) by the name of Baradagi. As an Argentinean poster (Fig. 2-01-001) expresses it, taking a jab at modern science, Baradagi/Varan “rose up from an underwater world to destroy a civilization that wanted to know too much.”

Figure 2-01-002

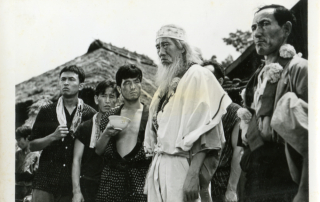

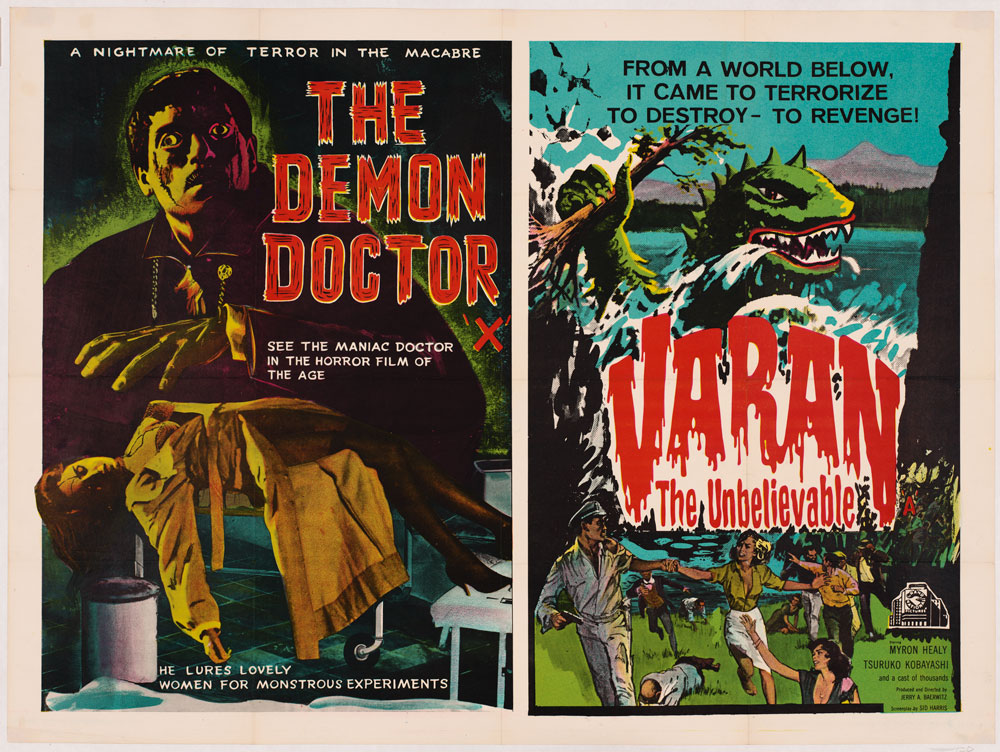

Echoing one of Gojira‘s more mystic moments, an early scene (Fig. 2-01-002) in Daikaijū Baran features a masked kagura ritual similar to the one that took place in Gojira on Ōdo Island. On a side note, it might be mentioned that in the case of both Godzilla (Gojira) and Varan (Baradagi), local inhabitants supposedly write the name of the monster-deity in archaic characters that mimic those of eighth-century Shinto mythology. For the average reader of Japanese, this subtle graphic touch conjures an aura of ancient mystery and quasi-religious awe. The characters for “Gojira” (呉爾羅), incidentally, appear only in the written screenplay and not in the actual movie, and have no particular significance apart from their phonetic value.

Although Tōhō had originally planned Daikaijū Baran as a four-part TV miniseries on order from, and destined for broadcast in, the United States, the television deal was ultimately cancelled and the teleplay became a theatrical release. The movie would indeed cross the Pacific, but in a form that differed markedly from what Japanese audiences had seen in their own theaters upon its domestic debut in 1958. Stateside producer-director Jerry Baerwitz (1925–2008) and scriptwriter Sid Harris, no doubt hoping to duplicate the 1956 success of King of the Monsters, reedited Daikaijū Baran extensively, adding new characters, new actors, and new scenes, while at the same time eliminating others. Crown International Pictures released the resulting feature to U.S. exhibitors in 1962. Despite these efforts, Varan the Unbelievable attracted far fewer viewers than King of the Monsters, nor would it, like its predecessor, play theatrically outside the Americas, with the exception of the U.K. (see Fig. 2-01-003). Paramount distributed the film in Argentina and Mexico.

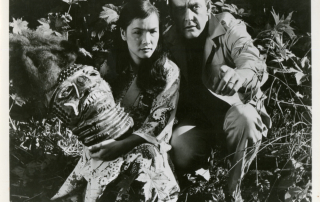

One feature that distinguished Varan the Unbelievable from the Japanese original, Daikaijū Baran, was its new male lead, played by Hollywood veteran Myron Healey (1923–2005). A U.S. lobby card (Fig. 2-01-004) shows Healey’s character, an American naval commander, in one of the Hollywood-filmed sequences, getting hit in the noggin by a bit actor wearing an unusual mask. In a related publicity still (Fig. 2-01-005), a similar object rests in the hands of Tsuruko Kobayashi, the Japanese-American actress whom Crown International hired to play Healey’s love interest. Both props are bizarre in style, in part a reflection of the fact that their Hollywood designers seem to have fused together Shinto-related visual elements from two separate sources in the original Japanese footage. Whereas the “masked worshipper” motif clearly draws inspiration from the kagura scene at Baradagi’s shrine, the actual features of the mask look nothing like those of the shaggy-haired worshippers at the ceremony. Instead, the face resembles—if you stretch your imagination just a bit—the sculpted image of Baradagi that stares out from beneath a sacred cordon (shimenawa) inside the shrine’s dark recesses during the same scene of the movie, like a fierce, if in this case entirely fictional, Shinto deity. The makeshift bust held by Kobayashi is a pale imitation of the more imposing religious icon of the original, Japanese-filmed sequence.

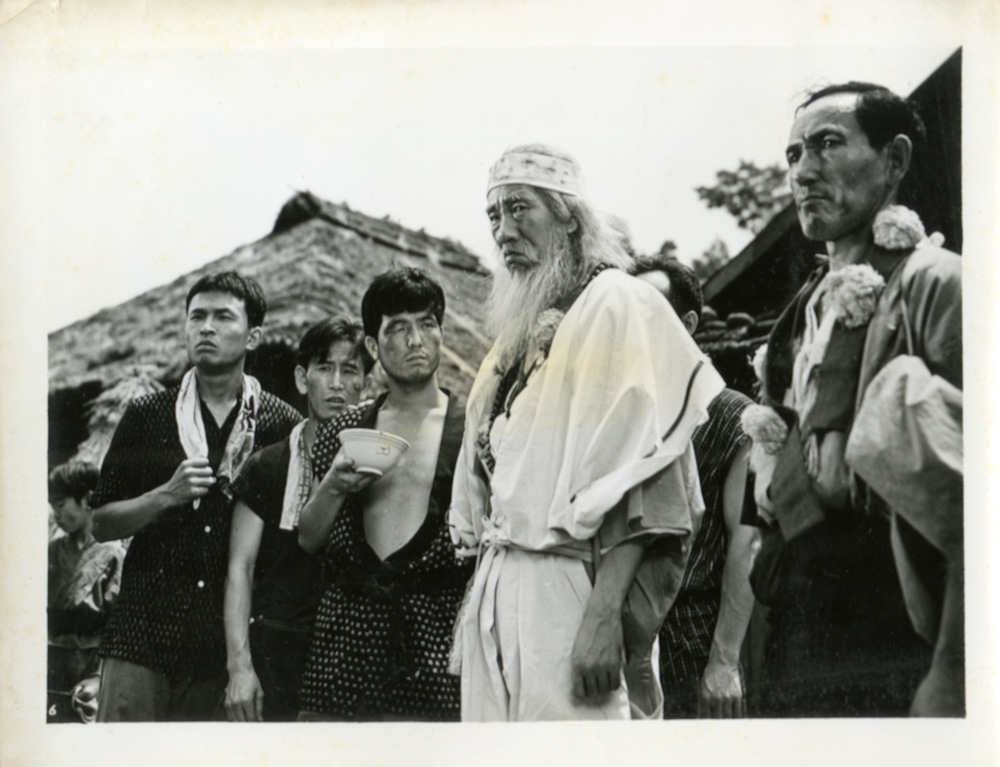

Daikaijū Baran and Varan the Unbelievable both give significant screen time to the chief priest of Baradagi’s shrine, played by SERA Akira (Fig. 2-01-006‘s white-robed man). He’s one in a long line of unnamed, but nonetheless memorable, Shinto and Shintoesque clerics who appear in kaijū eiga—although Sera’s character is probably the only one to be crushed onscreen by a monster, all the while brandishing a propitiatory wand of Shinto’s sacred sakaki tree. Strictly speaking, the priestly lineage starts with 1954’s Gojira, whose audience briefly glimpses, although it ultimately doesn’t learn much about, the seemingly elderly and male ritualist who presides over the kagura ceremony on Ōdo Island. Shaman-priests, stereotypically depicted with white hair and beard, flowing robes, neck beads, and rustic wooden staff, play a more conspicuous role in 1955’s Jūjin yukiotoko (reedited in Hollywood as Half Human [1958]) and 1958’s Daikaijū Baran, both set in isolated mountain villages in northeastern Honshu (the Tōhoku region).

Much like Shinto over the centuries, the kaijū eiga genre grants considerable power to shamanesses and other female spiritual figures. Prominent examples include the female spirit-medium (itako) of 1966’s Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster (U.S. title: Ebirah, Horror of the Deep) and the Okinawan high priestess—shown together with her high-priest grandfather on these Italian posters (Fig. 2-01-007, Fig. 2-01-008)—of 1974’s Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (U.S. title: Godzilla vs. the Cosmic [or Bionic] Monster). During the Sixties, as the makers of kaijū eiga recycled images of a “primitive” South Seas that were historically rooted in prewar colonialism, both Japanese and Western, exotically staged religious rituals by “native islanders” (as seen, for example, in this U.K. front-of-house still [Fig. 2-01-009] for 1962’s King Kong vs. Godzilla) became a staple feature of the genre, even as they left unchallenged Shinto’s fundamentally animistic worldview. Judging from the familiar garb he wears in this publicity still (Fig. 2-01-010), the tribal elder played by Japanese-Canadian actor Tetsu Nakamura in Tōhō’s 1970 feature film Space Amoeba (U.S. title: Yog: Monster from Space) might just as easily have been performing rites at a Shinto shrine in rural Japan as praying on the shores of “Sergio Island,” his fictional home in the South Pacific.

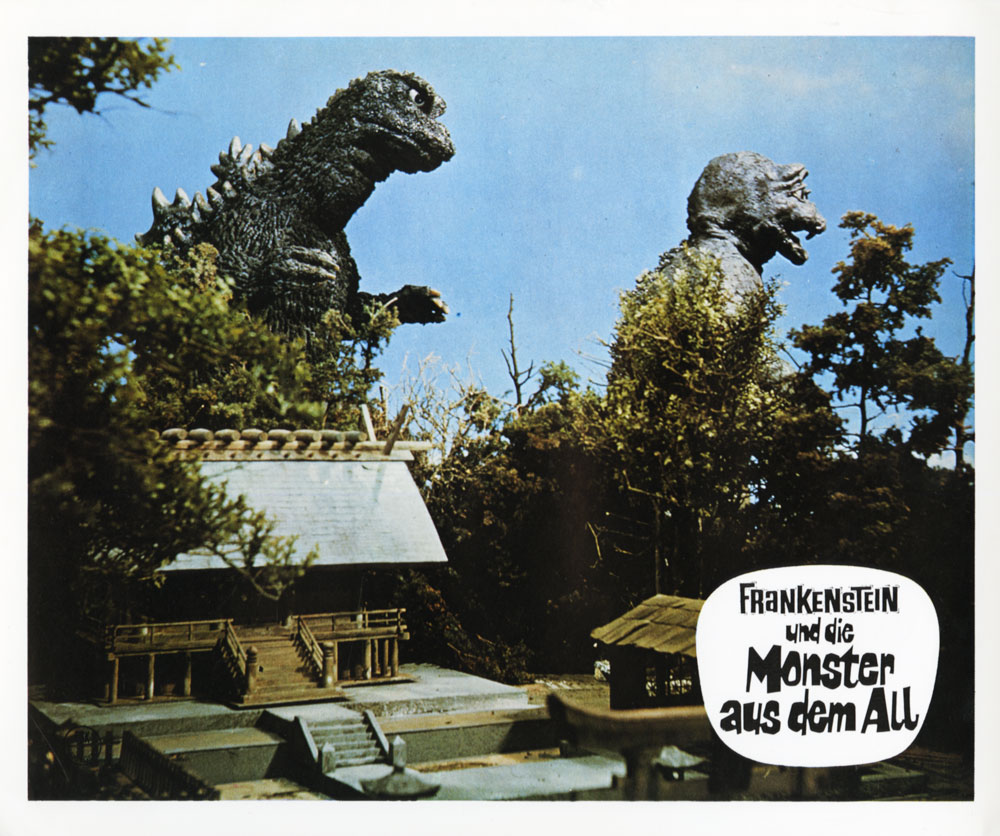

Although overseas moviegoers may not always have recognized them, Shinto symbols and artifacts literally littered the kaijū eiga‘s landscape. Even when dwarfed by Godzilla, the distinctively arched gate on top of the mountain in this U.S. promotional still (Fig. 2-01-011) from King Kong vs. Godzilla would have been difficult to overlook for any viewer raised in Japan. The same kind of gate, called a torii, appears in its customary location, the entrance of a Shinto shrine, on this publicity still (Fig. 2-01-012) for 1964’s Ghidorah [AKA Ghidrah], the Three-Headed Monster. The familiar architectural detail infuses the miniature landscape with a sense of everyday peace and calm, as well as of “Japaneseness,” that contrasts effectively with the violent, extraterrestrial nature of Ghidorah, the monster framed inside. A Shinto shrine similarly occupies the foreground in a West German lobby card (Fig. 2-01-013) for Destroy All Monsters (1968), or as the movie was called in German, “Frankenstein and the Monsters from Space.” The auspicious landmark bodes good fortune for Godzilla and Minilla, the father-and-son kaijū in the background, who march toward Mt. Fuji—which is not only a globally familiar emblem of Japanese tradition but also a Shinto holy site (the mountaintop torii of King Kong vs. Godzilla sits, in fact, on Fuji’s summit)—to protect Japan and the world from the alien Ghidorah’s ravages. As was not infrequently the case with publicity images that circulated overseas, the orientation of the photo somehow got reversed in the course of its international travels (compare with the Japanese lobby card in Fig. 2-01-014).

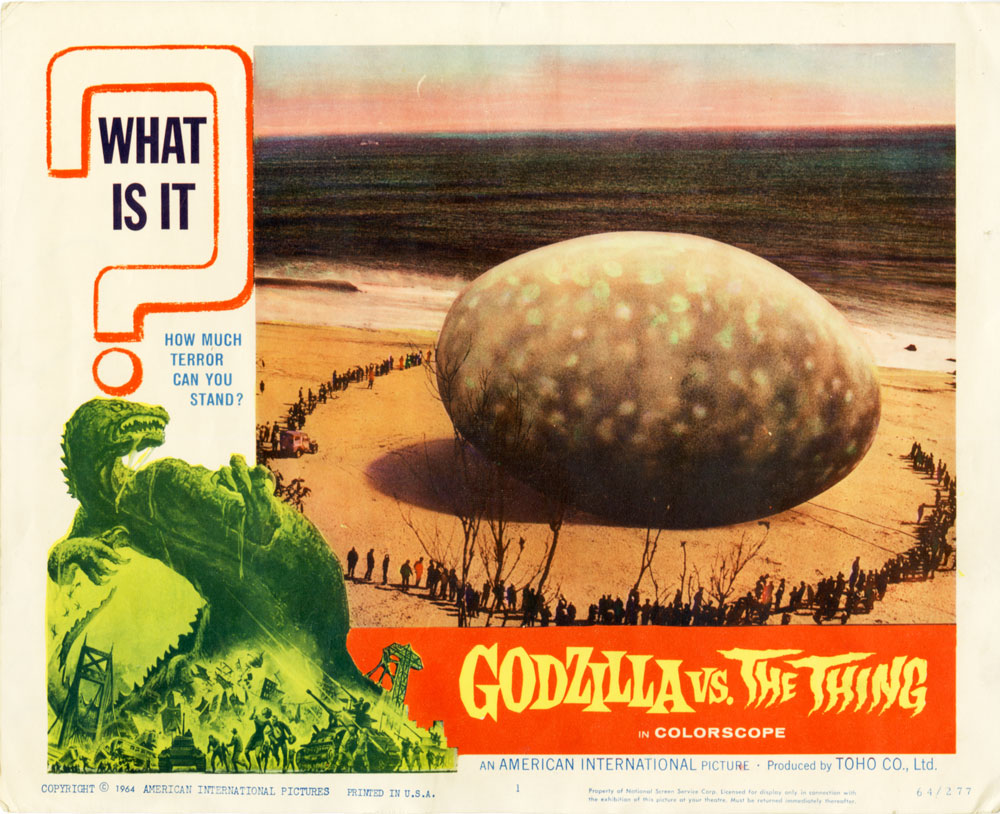

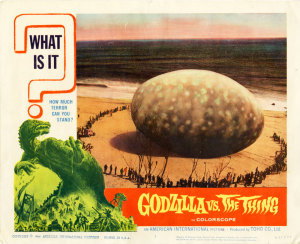

Figure 2-01-015

Here’s one final example of Shinto sensibilities and symbolism. In an early scene of 1964’s Mothra vs. Godzilla (U.S. title: Godzilla vs. the Thing), a group of rural Japanese spot a “monster egg” (tamago no bake) floating off the shore of their coastal community. Before they venture to approach the strange object, they make sure that a Shinto priest has performed a sort of ritual blessing known as oharai, complete with much waving of his sacred sakaki wand. A U.S. lobby card (Fig. 2-01-015) shows the giant egg ringed by inquisitive locals; later in the movie, a larval Mothra will break out from inside the shell. The circle formed by the onlookers, meanwhile, is reminiscent of the sacred perimeter that normally surrounds Shinto holy sites and objects, often cordoned off by a special kind of rope known as a shimenawa. It also makes for an amusing echo of the egg’s own form.

To say that native spiritual traditions played a role in shaping Godzilla [VISUAL SIDEBAR 1: Gods and Monsters] doesn’t mean that fantasy films made in Japan are any more fundamentally informed by religion or folk belief than their counterparts elsewhere. It just makes them differently so. Let’s not forget that the sci-fi features Hollywood produced during the Fifties similarly reflected the Judeo-Christian heritage of their makers, whether they did so on an explicit or an implicit level. Critics often cite, for example, the Messiah-like qualities of the extraterrestrial character Klaatu in 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still, whose Earth name, Mr. Carpenter, echoes the livelihood of another messenger of peace (in case you need it spelled out: Jesus of Nazareth) who claimed provenance from a different world. And who can forget the closing lines of the 1953 version of War of the Worlds? After the Martian spacecraft have crashed to the ground, their pilots having succumbed to terrestrial bacteria, the narrator solemnly intones, “After all that men could do had failed, the Martians were destroyed and humanity was saved by the littlest things, which God in His wisdom had put upon this Earth.” A deus ex machina, if ever there was one.

Let’s return, though, to Ōdo Island. Godzilla’s first appearance takes place in a geographic setting [VISUAL SIDEBAR 2: Godzilla’s Pacific Playground] that’s fictional but telling. Although Ōdo exists nowhere on actual maps, some details of the film Gojira, along with its successors, point to a possible location in or near the Ogasawara Islands, which can be found in the northwest quadrant of the Pacific Ocean, several hundred kilometers off Japan’s southern coast. Alternatively, Ōdo may lie a bit farther northward, perhaps in the Izu chain. Both the Izu and the Ogasawara Islands today form part of Japan proper, although they’re administrative oddities that fall officially within the city limits of Tokyo, several degrees of latitude to the north. During the twentieth century, Japanese anthropologists and other scholars often traveled to such peripheral areas as the Izu Islands to study what they believed to be the lingering cultural origins of their own “island country” (as Japanese people are fond of calling their sea-encircled nation).

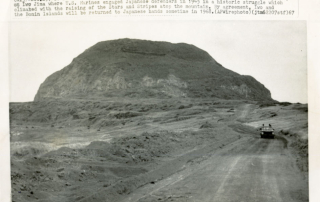

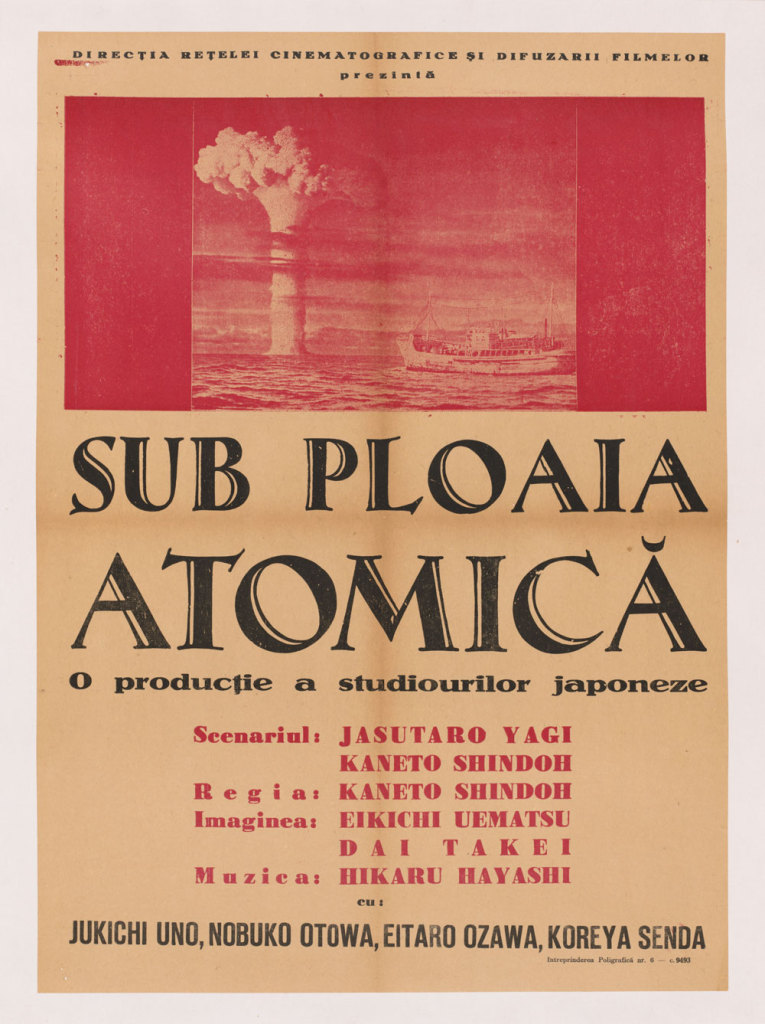

In the first entry of the Godzilla film cycle, the monster approaches Japan’s main islands from a southerly direction and gradually closes in on Tokyo, the nation’s capital. Gojira (1954) thus marks its title creature as a child of the Pacific as well as, historically speaking, of the Pacific War. American B-29s had followed the same northward trajectory on their bombing sorties to Tokyo from Saipan, an island that Japan controlled since World War One but which was overrun by Allied forces in July 1944. By February 1945, Yankee troops had reached Iwo Jima, a speck of land that forms part of the Ogasawara chain—and more specifically, of its Volcano Islands subgroup—an integral part of Japan since the late nineteenth century. North of the Ogasawara chain lie the Izu Islands, and to the north of them Tokyo proper.

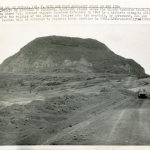

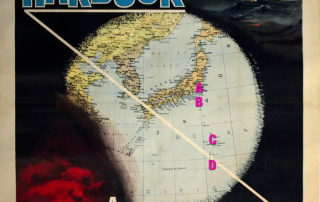

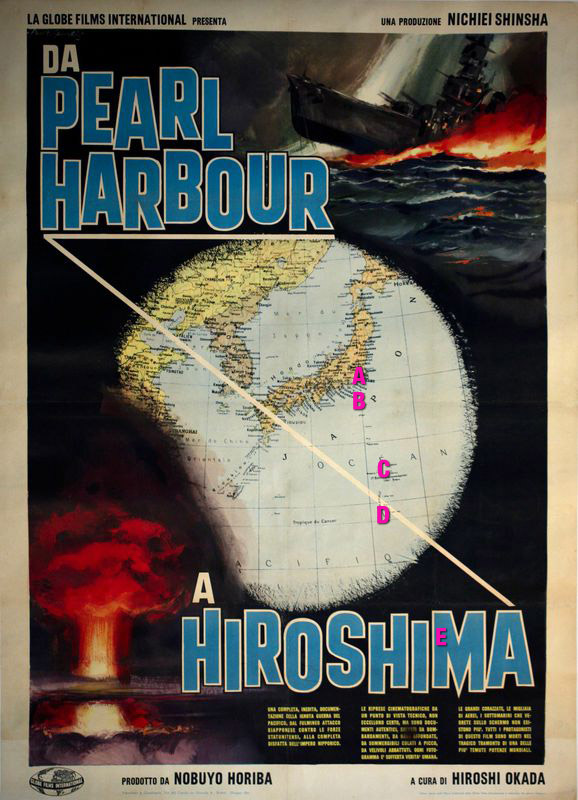

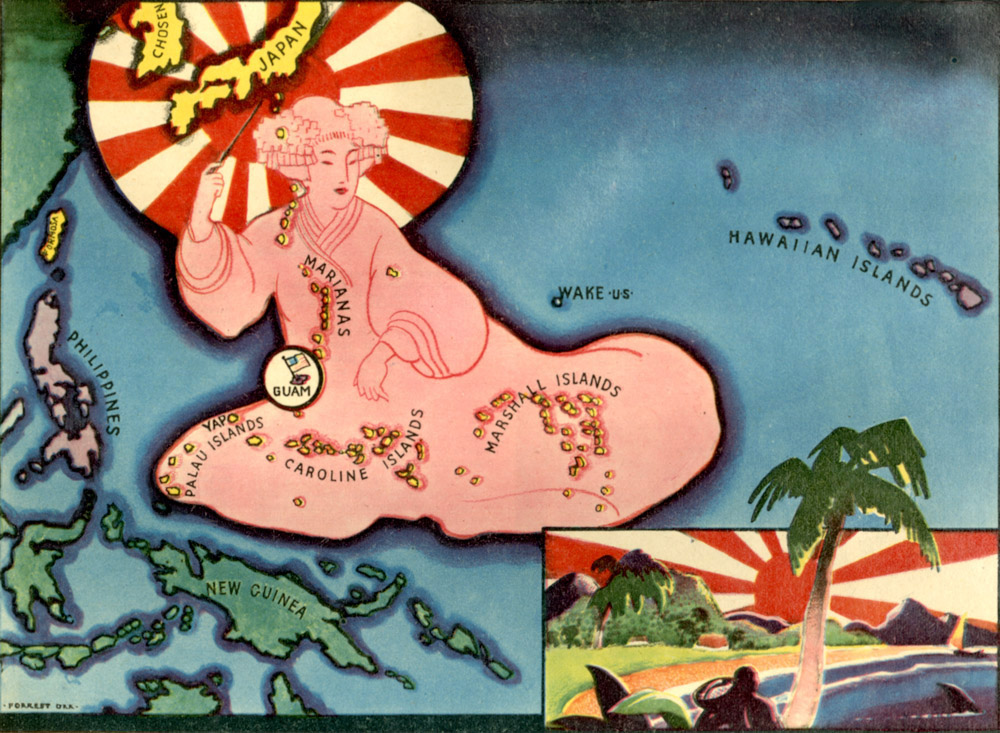

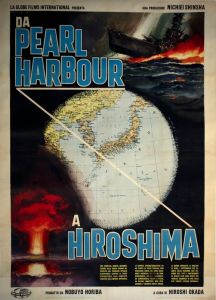

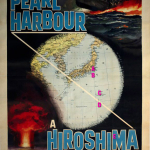

Figure 2-02-001

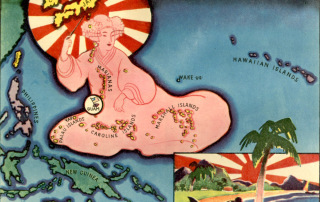

Godzilla’s destructive course can be conveniently tracked on an Italian poster (Fig. 2-02-001) for Taiheiyō senki (Record of the Pacific War), a 1958 Tōhō documentary that traced the historical path, as the Italian title puts it, “from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima.” Downtown Tokyo lies at point A, the Izu cluster roughly at point B, and the Ogasawara archipelago roughly at point C, with Iwo Jima, a bit of an outlier, at point D. The dark area outside the circle obscures the more southerly location of the Mariana Islands, with point E corresponding to Saipan. Roughly level with the word HIROSHIMA, but at a considerable distance beyond the right edge of the poster, lie the Marshall Islands, the primary Pacific site of Cold War nuclear testing by the United States. The diagonal white line, if extended, would pass close by Bikini (today’s Pikinni) Atoll in the Marshalls, where Godzilla possibly got his first whiff of radiation. An American newspaper illustration (Fig. 2-02-002) from 1936 offers a graphic sense of Japan’s former colonial presence in the region.

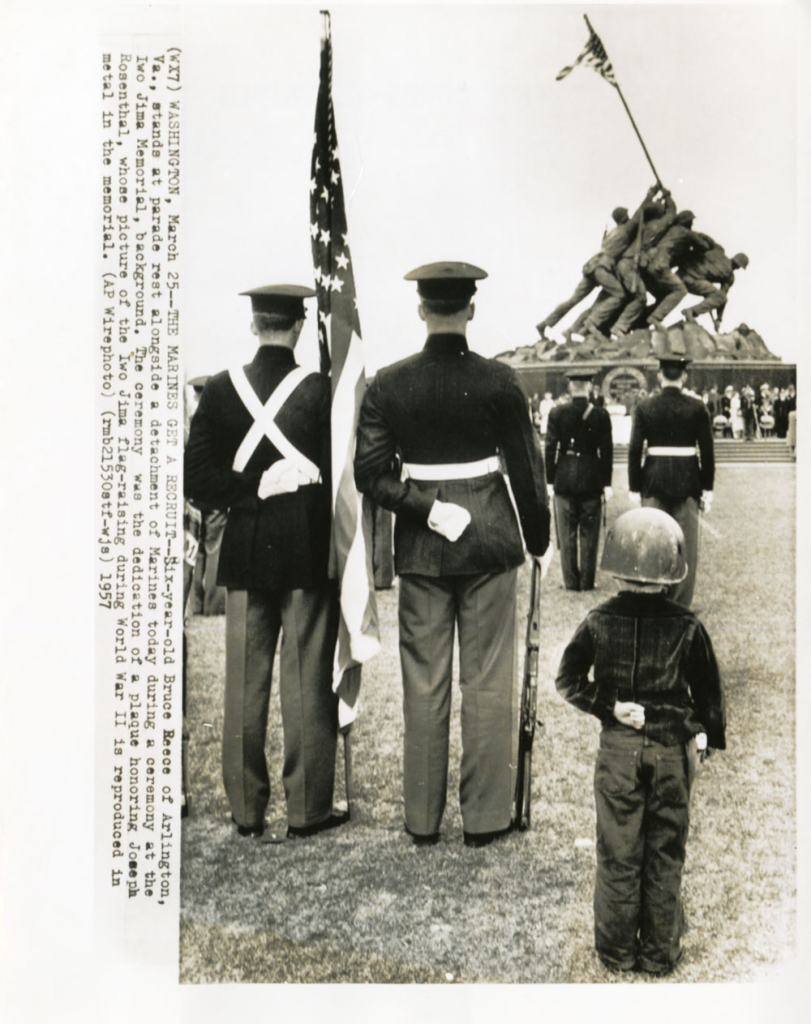

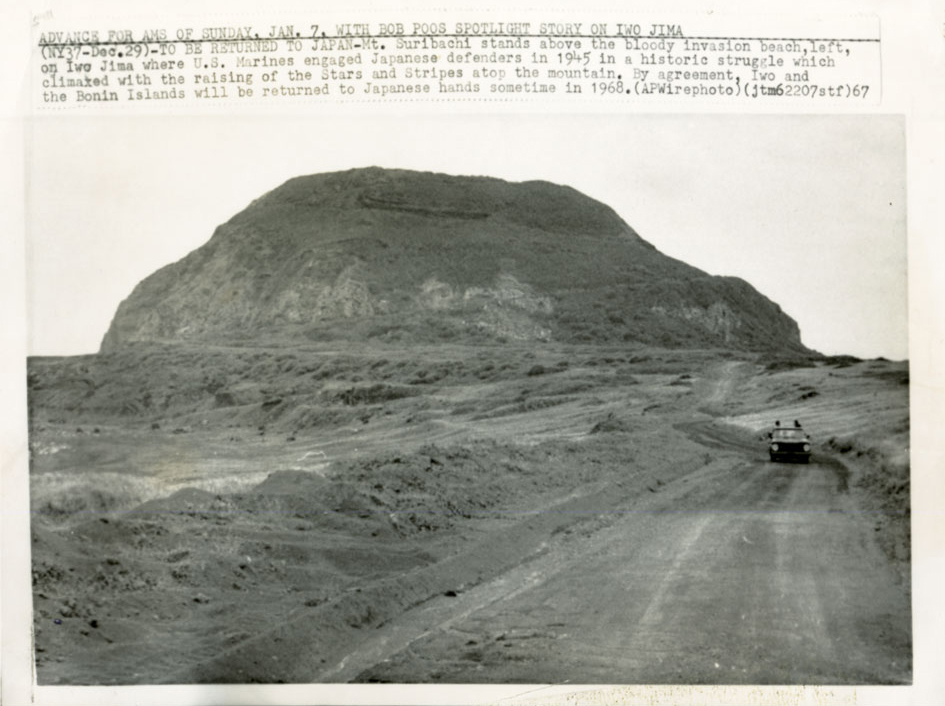

For postwar Americans, the best known of these Pacific locales was undoubtedly Iwo Jima, which rises from the ocean at the southern end of the Ogasawara chain. The celebrated photograph, by Joe Rosenthal (1911–2006), of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima’s Mt. Suribachi on February 23rd, 1945, became iconic in America almost overnight. Even so, during the Golden Age of Hollywood, a still image, or even a living tableau of the scene (Fig. 2-02-003), couldn’t be expected to compete with a motion picture. Four years after the historical event, a cast that included three of the original participants in the flag-raising recreated “the Marines’ greatest hour” in Republic Pictures’ Sands of Iwo Jima (1949; Fig. 2-02-004). Although John Wayne was already an experienced actor at the time, his lead role in the feature won him his first Oscar nomination.

Joe Rosenthal’s classic photograph later provided the basis for the United States Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia, whose dedication took place just a week after Gojira‘s Tokyo premiere. A wire photo (Fig. 2-02-005) from the files of the San Francisco Examiner shows a ceremony honoring Rosenthal held at the Memorial in March 1957. The figure of the six-year-old boy standing at “parade rest” next to two adult Marines silently captures the sense of patriotism that Iwo Jima had come to evoke in postwar American memory.

After the Pacific War ended, Hollywood’s marketing power overseas meant that American depictions of that conflict, including the Battle of Iwo Jima, lit up movie screens on every continent. The defeated nations of the former Axis were no exception. Sands of Iwo Jima played in Austrian, Japanese, and West German theaters in 1952, the same year that Japan emerged from Allied Occupation. Rather diplomatically, a Japanese poster (Fig. 2-02-006) describes Sands of Iwo Jima as a “controversial war epic.” The movie’s original English-language dialogue referred frequently to “Nips,” but in fact the Japanese military barely appears in the film at all. In that respect, the story accurately reflects the experience of American soldiers on the island, who rarely saw—alive, at least—the entrenched foe whom they were fighting.

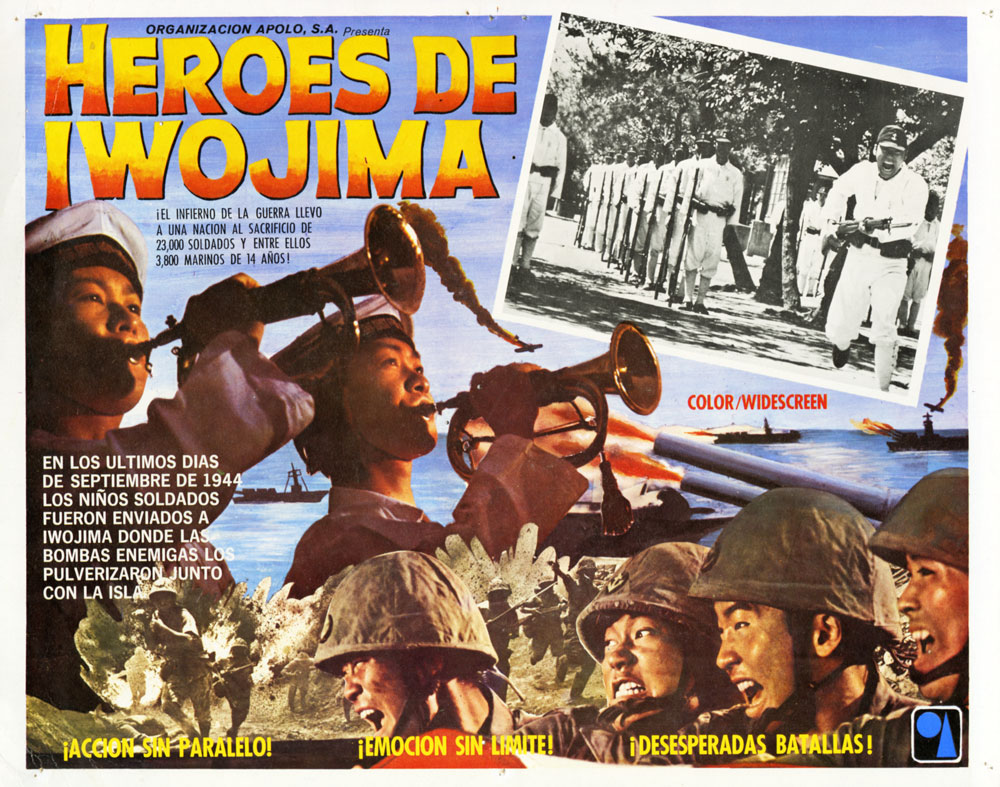

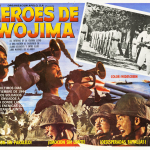

Figure 2-02-007

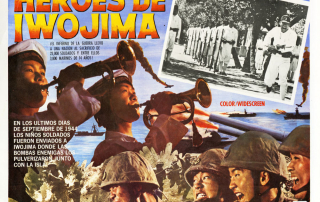

It’s only fairly recently that non-American perspectives on Iwo Jima have begun to reach movie screens outside Japan, most notably in Clint Eastwood’s Oscar-winning Letters from Iwo Jima (2006). An earlier exception to the rule, this one the product of a Japanese studio, may be found in Iōjima (Iwo Jima), a 1959 release from Nikkatsu. Iōjima got little, if any, play in English-speaking countries, but it did wind up on screens in Mexico. It’s important to note that the “Heroes of Iwo Jima” to whom the Mexican title refers aren’t GIs, but instead young Japanese conscripts who, according to the text on the lobby card (Fig. 2-02-007), “in the last days of September 1944 were sent to Iwo Jima where enemy bombs pulverized them and the island.” Another tagline on the card proclaims sympathetically: “The inferno of war led a nation [i.e., Japan] to sacrifice 23,000 soldiers, among them 3800 fourteen-year-old youths.” It’s hard to imagine a publicity campaign mentioning Americans only as the “enemy” selling many tickets north of the Rio Grande. Even in the twenty-first century, producer-director Clint Eastwood felt it wise to prepare American audiences for his Letters from Iwo Jima by first releasing its Yank-centered companion piece, Flags of Our Fathers (2006). Appropriately enough, Flags of Our Fathers was based on a nonfiction bestseller authored by the son of one of the real-life flag-raisers who had appeared in 1949’s Sands of Iwo Jima.

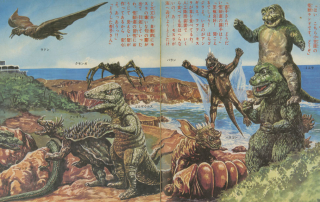

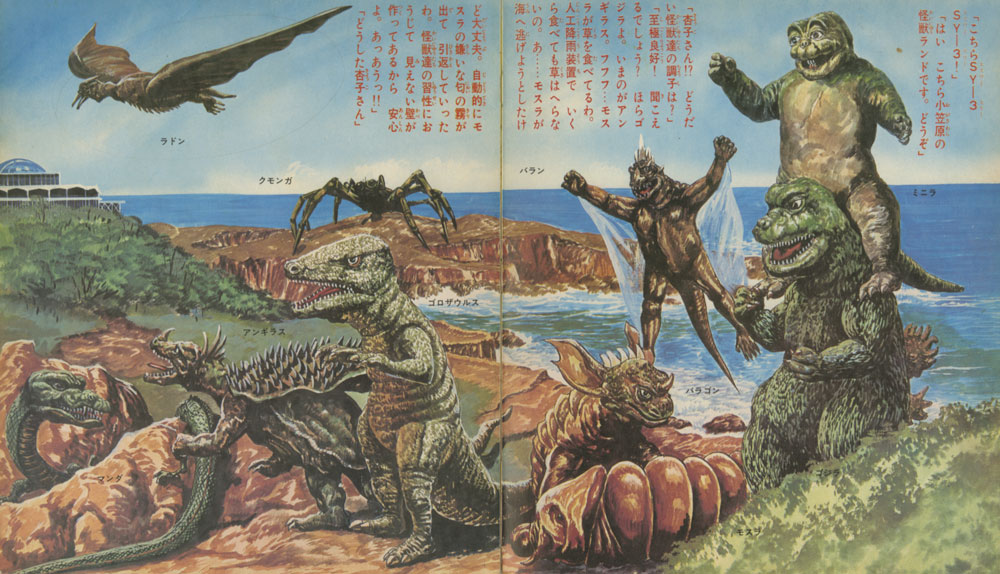

Within the Godzilla film cycle, audiences first hear the names of Iwo Jima and Ogasawara explicitly mentioned—as opposed to being gestured at ambiguously—in 1968’s Destroy All Monsters. It’s no coincidence that the islands had reverted to Japanese sovereignty just five weeks before the movie’s release. (For a related news photograph, see Fig. 2-02-008.) After 1968, monsters took over from American occupiers as the Ogasawara chain’s most exotic residents, at least in the imagination of a certain generation of Japanese youngsters. A children’s-book version (Fig. 2-02-009) of Destroy All Monsters published in Japan in 1971 colorfully conveys that fantasy. Accompanying the picture book was a 33-⅓ RPM flexidisc, one of those thin, floppy but fully playable phonograph records that publishers of the past sometimes inserted in books or magazines as a bonus for readers. The creatures shown in the two-page illustration of “Monsterland,” supposedly located somewhere in the Ogasawara Islands, are, from left to right: (top row) Rodan, Kumonga, Varan, Minilla; (bottom row) Manda, Anguirus, Gorosaurus, Barugon, Mothra (in her larval form), and Godzilla.

American International Pictures’ 1969 Stateside release of Destroy All Monsters began—memorably for me—with the following English-language narration. “The year is 1999…. An underwater base was recently established near Ogasawara Island [NB: it isn’t clear exactly which of the various islands of the Ogasawara chain the AIP dubbers had in mind, if any] and scientists are studying the habits of marine life. New kinds of fish are being bred here, while on land, all of the Earth’s monsters have been collected and are living together in a place called Monsterland: Godzilla, Rodan, Anguirus, Mothra, and Gorosaurus. If the monsters try to leave the spaces provided for them, a special control apparatus goes into operation. They are confined within scientific walls, each according to their own instincts and habits…. There is food in abundance here, and the monsters are free to eat as much of it as they please.”

To this idyllic description of Monsterland, the original Japanese version of the film, however, had added one further geographic detail. In this future age, the Japanese narrator informed audiences, nearby Iwo Jima was functioning as a launching station for international moon rockets. By situating the fictional spaceport in such a historically sensitive and significant place, the original creators of Destroy All Monsters were likely trying to suggest that the nations of the earth must set aside their enmities and learn to live in harmony. Even the mention of Iwo Jima, however, had the potential to spoil the fun for Americans of the postwar era. Accordingly, although the Stateside release briefly showed audiences the space center, AIP dubbers decided to omit Iwo Jima’s all-too-familiar name.

At the same time, the Izu and Ogasawara Islands, if followed to the south, form steppingstones to Micronesia, and to a broader oceanic realm that many ordinary Japanese of the twentieth century imagined as a backwater of primitiveness in the modern age. Between the First and Second World Wars, Japan ruled the scattered islands of Micronesia as a colonial mandate, the official name of which, Nan’yō, simply meant “South Seas.” During the latter conflict, fierce fighting took place in both Micronesia and the Ogasawara Islands. One of the southernmost specks of land in the Ogasawara group is the volcanic Iwo Jima, site of what remains for Americans one of the emblematic battles of the Pacific conflict. Although the Allied Occupation of Japan ended in 1952, two years before Gojira was released, the American military continued to administer the Ogasawara Islands (which it called the Bonin Islands) for another fifteen years. It’s odd—or perhaps not so odd—that Gojira‘s screenplay makes no mention of this foreign occupation going on so close, ostensibly, to Godzilla’s birthplace.

Ōdo Island, where Godzilla makes his first landfall, thus straddles a threshold between past and present. It holds reminders both of ancient tradition and of a catastrophic global conflict that was still fresh in the memory of Gojira‘s original audience. Similarly, the fictional island appears to lie both within and outside of Japan. On the one hand, it’s the dwelling place of kami, and its residents worship the deities of nature according to Shinto ritual. For example, locals call the mountain over which Godzilla first rears his head Hachiman-yama, after a fearsome war god in the Shinto pantheon. Ōdo’s human inhabitants also bear Japanese names and speak the Japanese language. On the other hand, the island’s geographic location points subtly to a set of recent historical circumstances that have brought into question the very sovereignty of Japan as a nation. Godzilla makes his first film appearance in a curious overlap between Japanese and American territories and histories. But his influence would eventually extend much farther.