CONTINUED FROM MODULE 1 PART 2

GODZILLA AND THE VISUAL ENVIRONMENT

Compared to most movie monsters born in the Fifties, Godzilla has enjoyed an unusual longevity. Part of the secret may lie in the creature’s inability, or at least his reluctance, to speak. Because Godzilla lacks the words to tell us his own story, we read into his glowering eyes any number of wishful fictions.

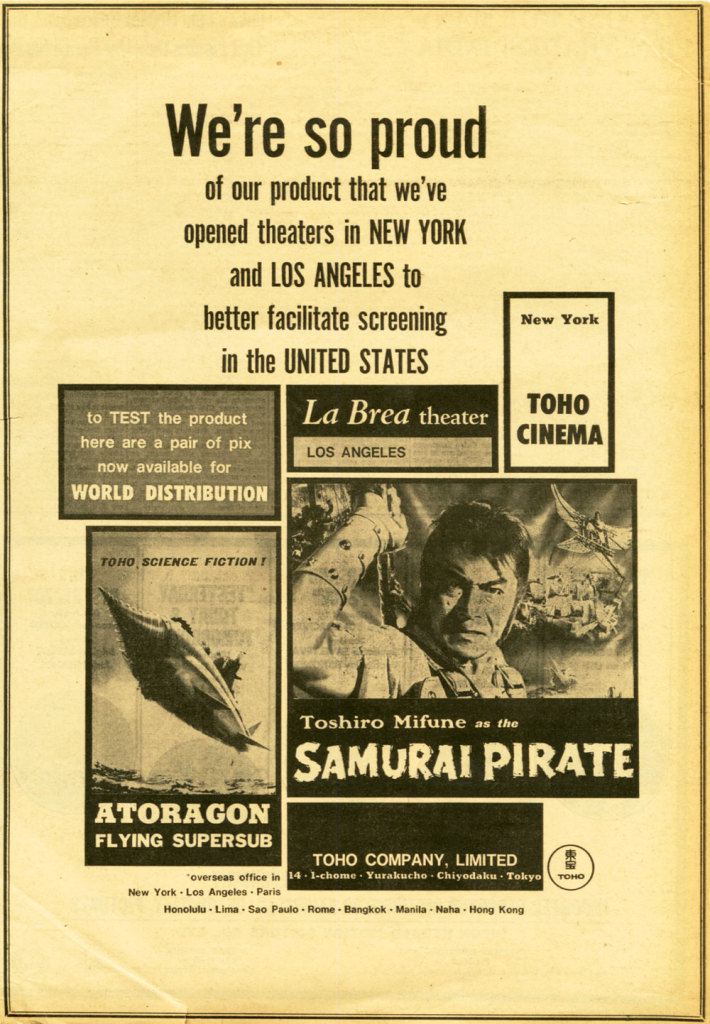

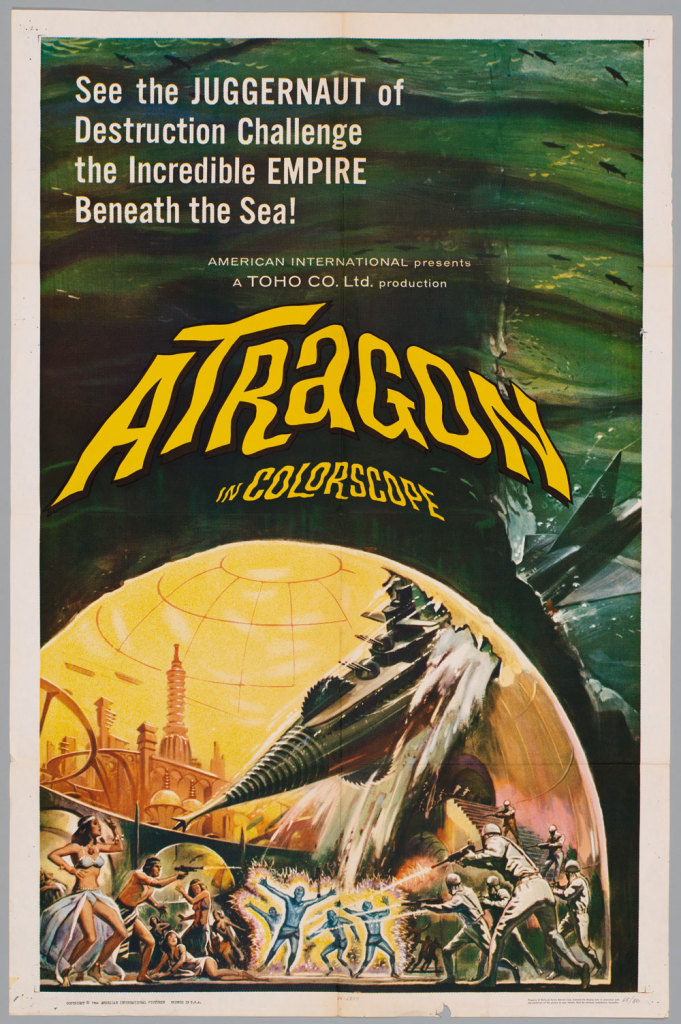

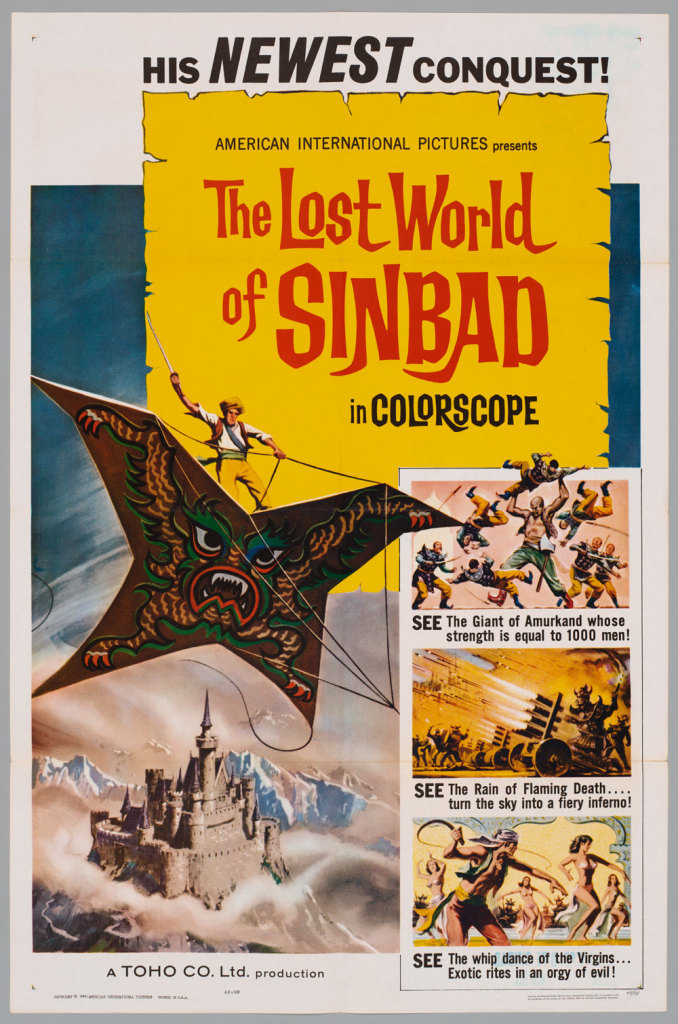

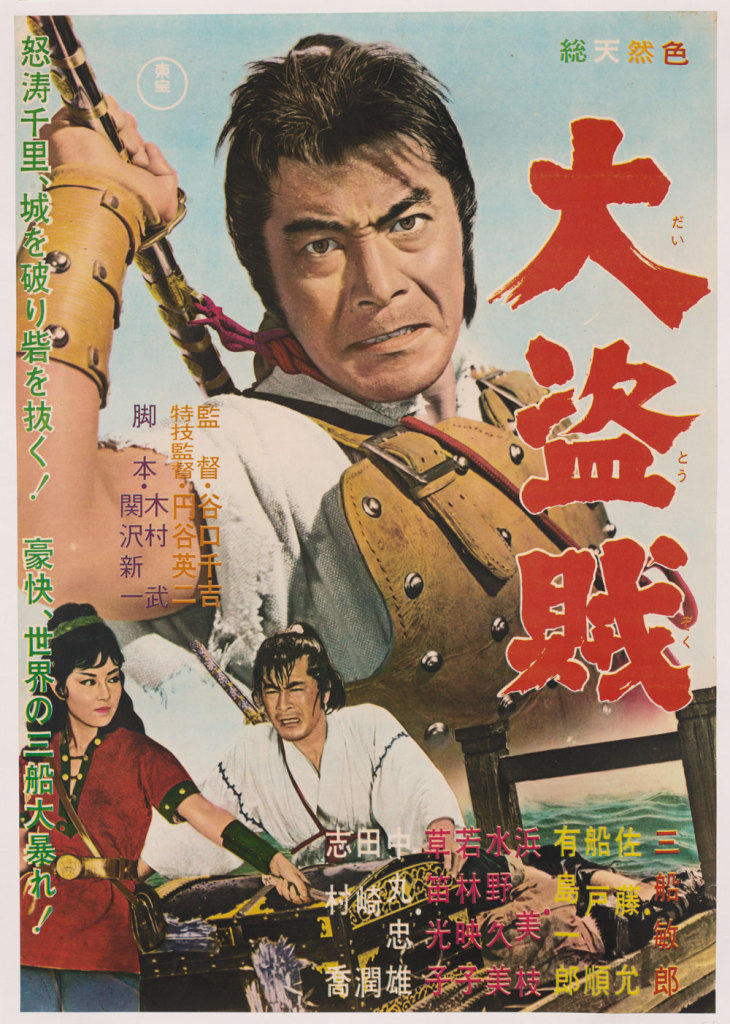

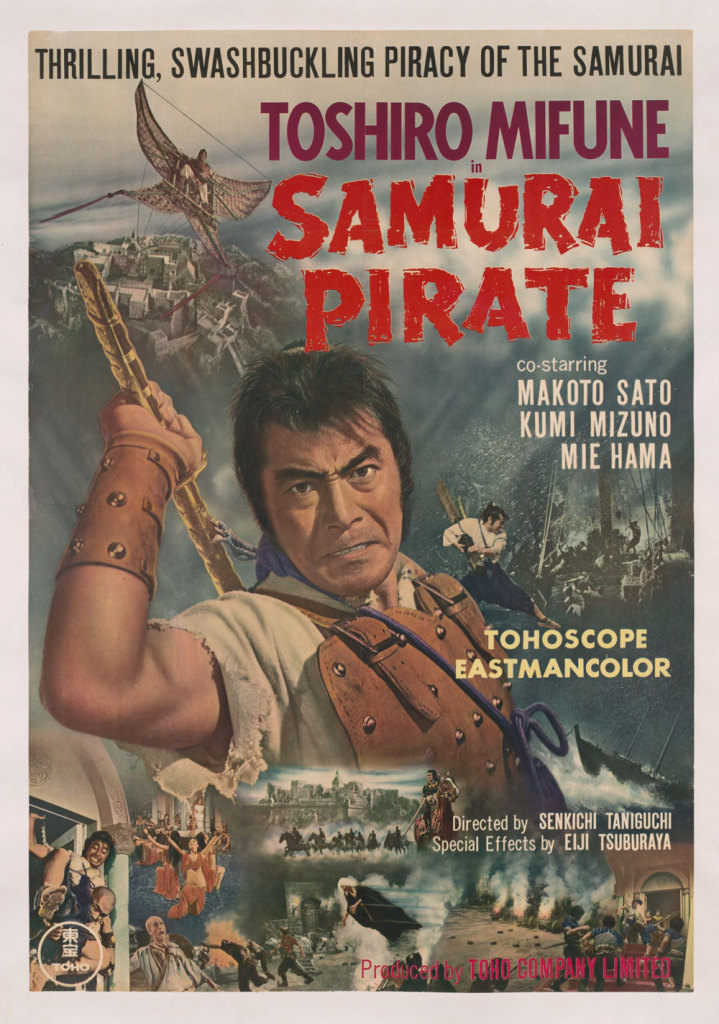

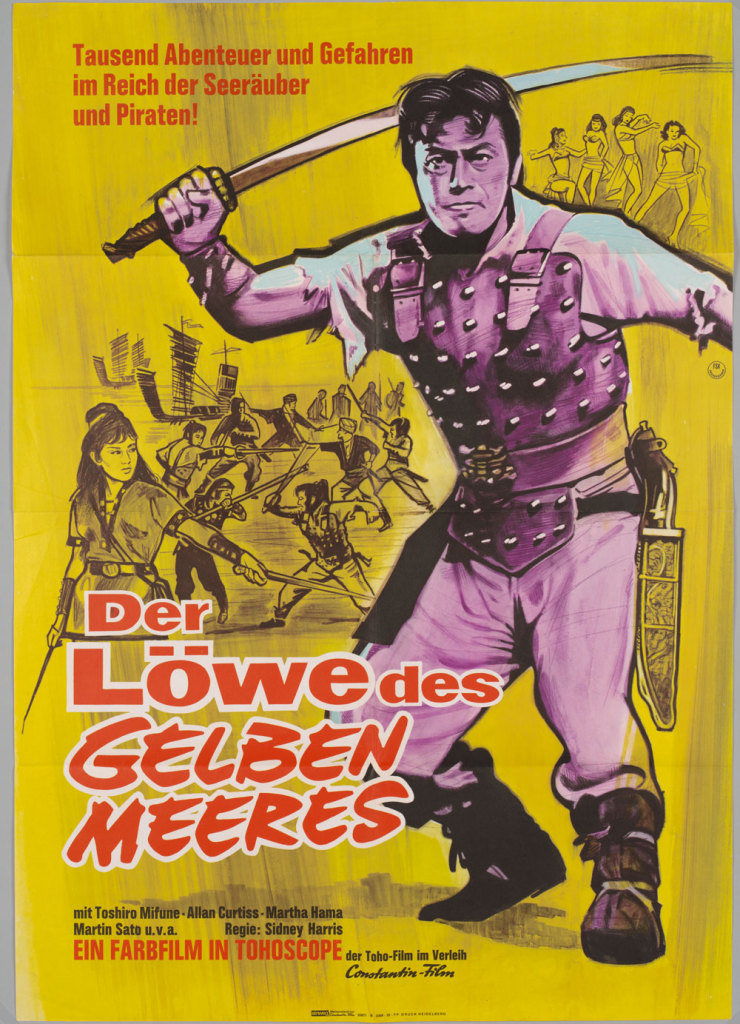

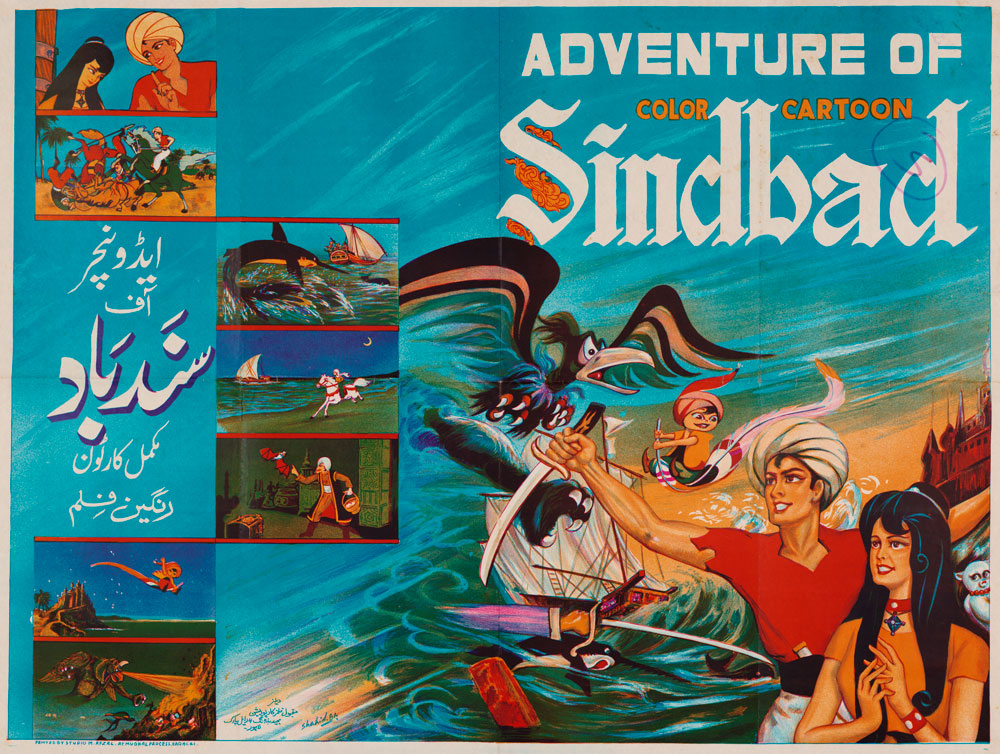

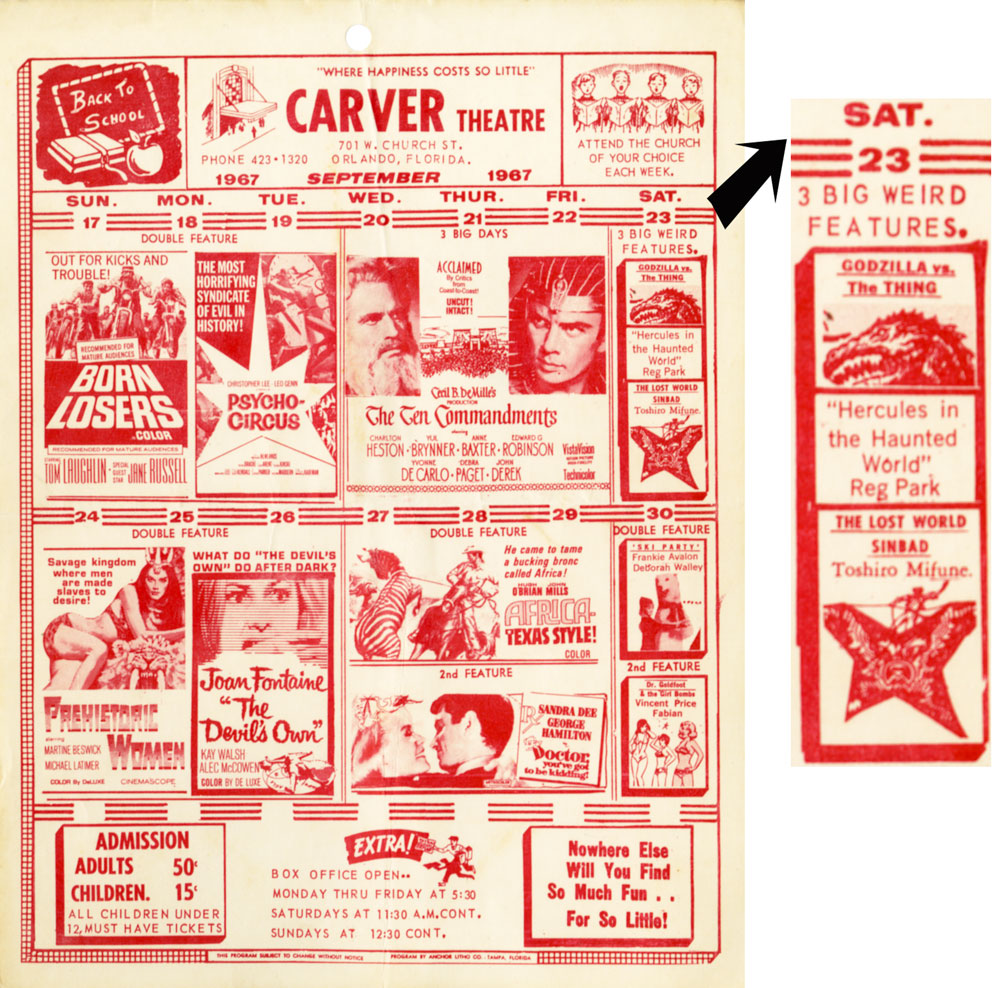

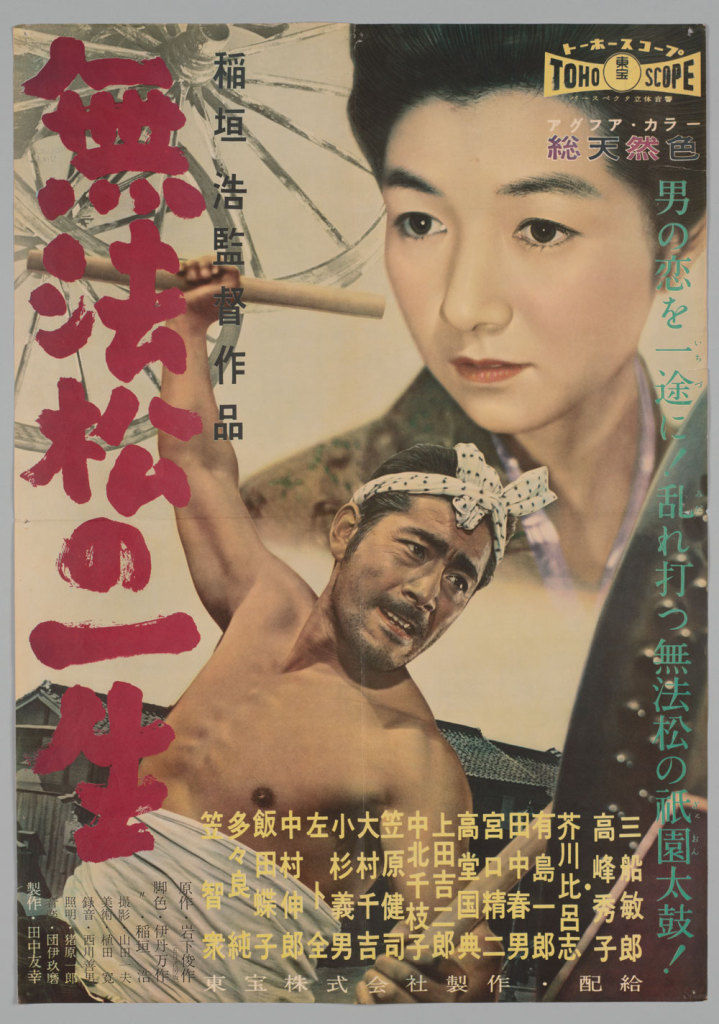

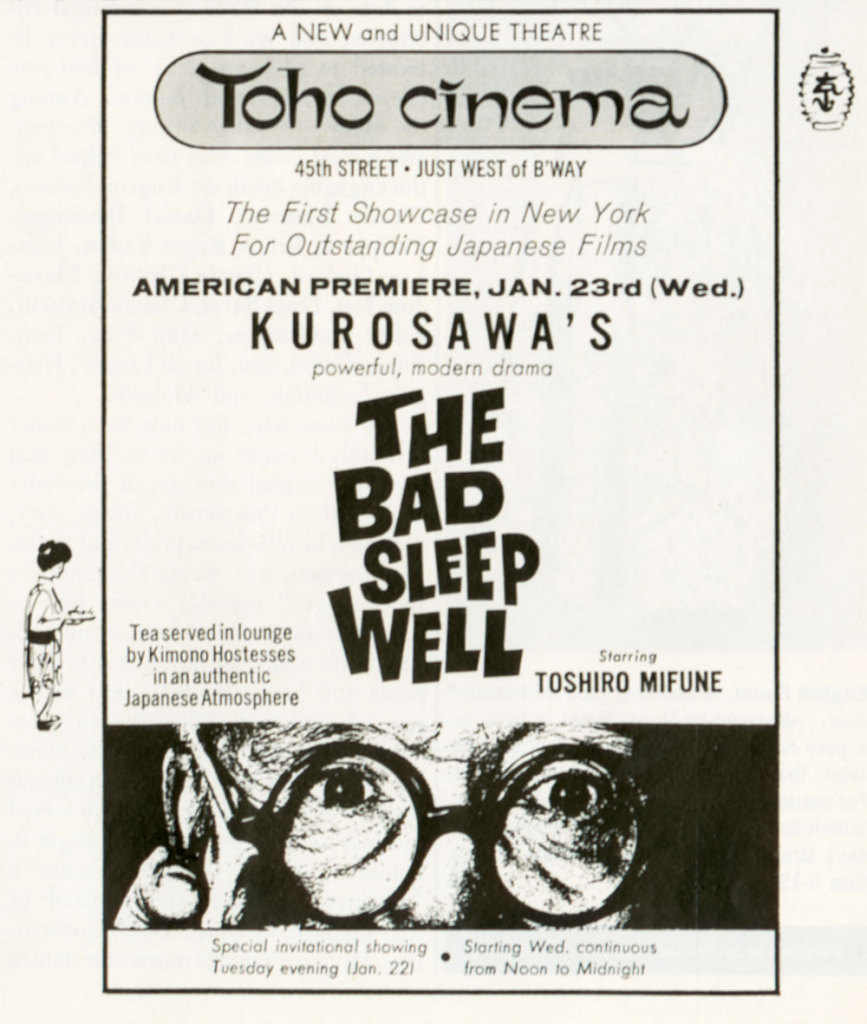

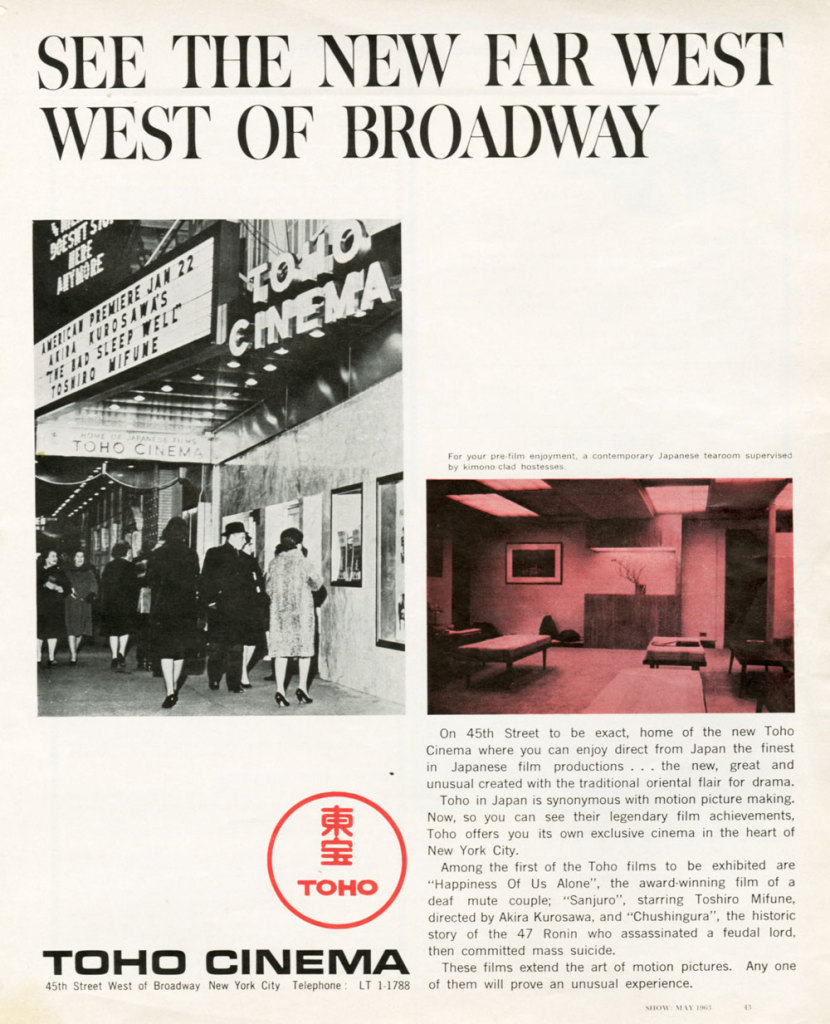

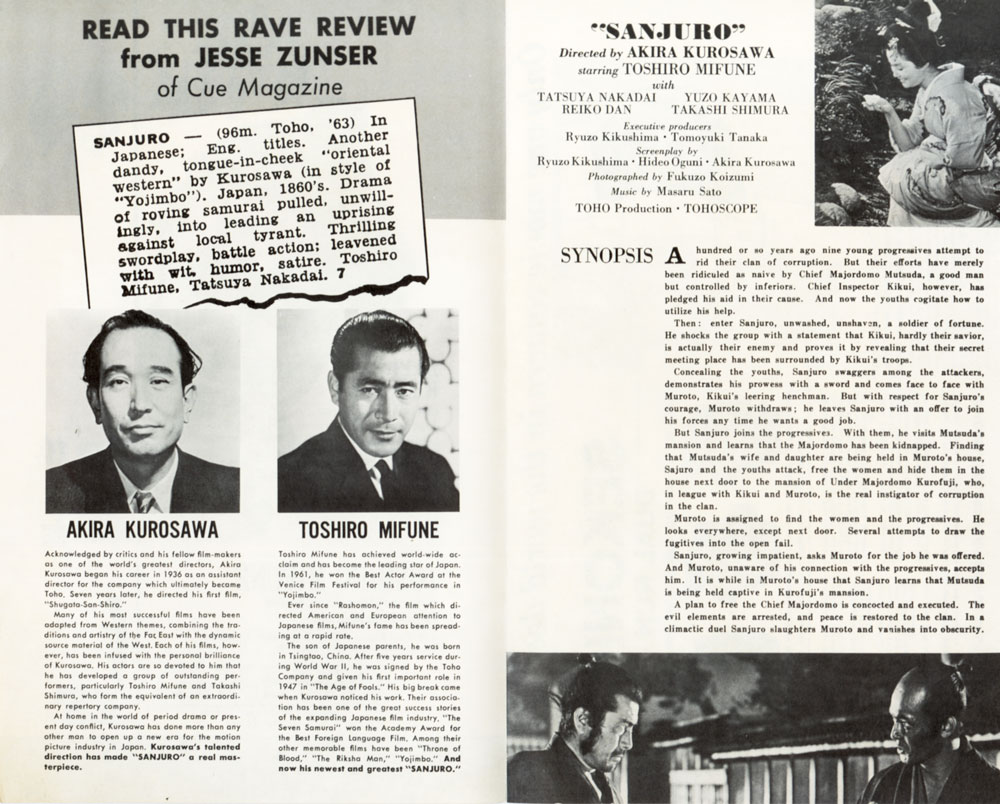

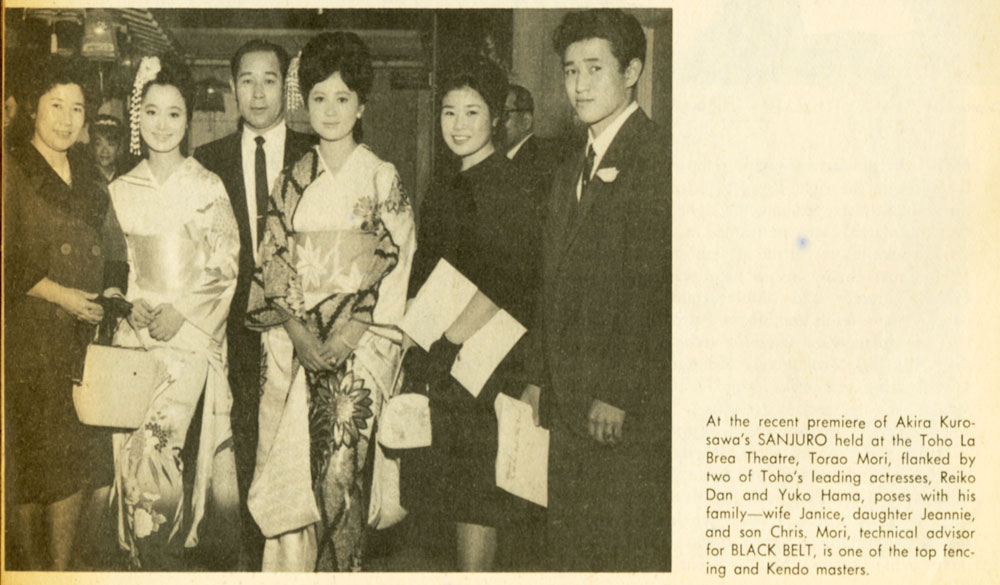

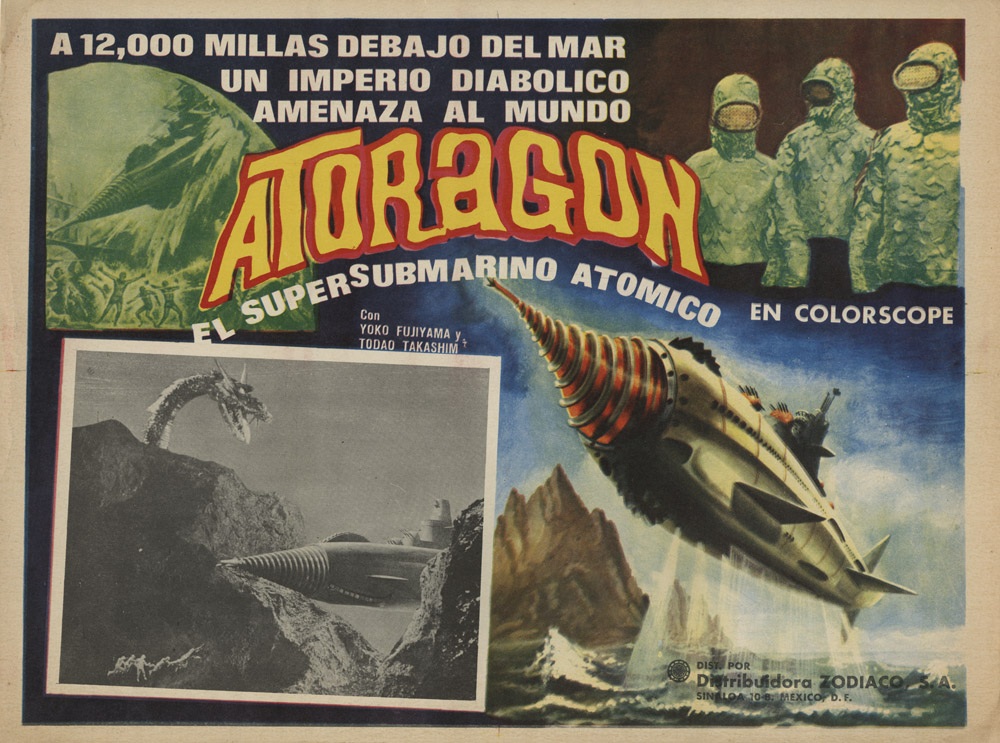

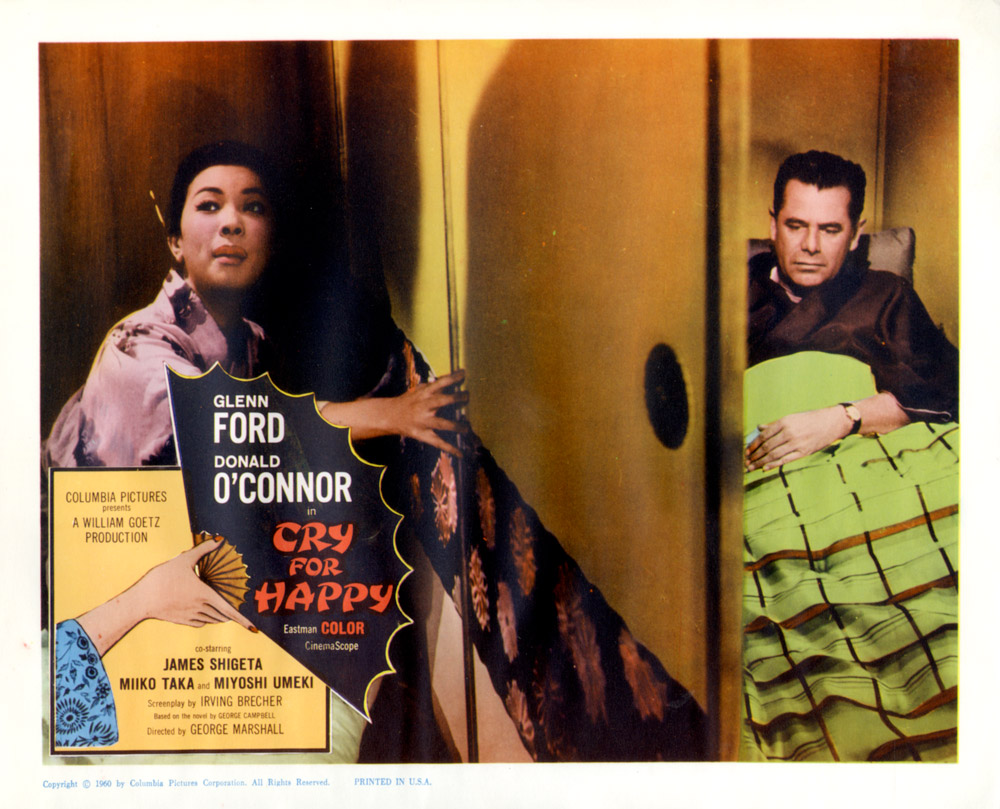

Over the six-plus decades of his existence, Godzilla has relied more heavily on visual than on auditory communication. To be sure, the earth-pounding beast has let forth more than one soulful roar in the course of his film career, and mesmerizing soundtracks by such talented composers as IFUKUBE Akira (1914–2006) have left an emotional imprint on movie viewers in their own distinct ways. Nevertheless, most people’s first encounter with a screen icon like Godzilla is a visual experience. It usually takes place long before they enter the theater, or flip on their televisions and tablets. The commodity of film entails much more than simply “celluloid” (which is no longer the recording medium of choice, in any case). It’s part of, and dependent on, a larger system of images, objects, institutions, and practices that determine the course of its circulation and the meanings it ultimately conveys to audiences. In capitalist economies especially, the carefully coordinated and systematized marketing process that goes by the name of promotion (or more evocatively, “exploitation”) can affect the impact and success of a film just as much as its content. Publicity posters, billboards, trailers, television commercials, newspaper ads, lobby displays, and other visual materials are the stuff of film promotion, and they go a long way toward shaping the expectations and experiences of movie viewers. A clever advertising campaign won’t necessarily turn a dud into a blockbuster, but it may usher considerable numbers of paying customers through the theater doors.

The visual materials reproduced here consist mainly of film posters and other kinds of two-dimensional, still images that were created over the years in order to market Godzilla and his fellow kaijū to audiences outside Japan, or that otherwise shaped their local reception. They originate from over three dozen countries on six different continents and span the more than half-century since Godzilla’s birth, focusing especially on the Fifties through the mid-Seventies. As promotional materials, they necessarily bear a relationship to the moving imagery of the films they were meant to publicize. Nevertheless, the connection of the publicity images with the content of their respective films varies and, at times, it can be quite tenuous. It’s best to understand the realm of the publicity image as operating according to a visual logic of its own. It also needs to be acknowledged that although the visual materials I focus on here are, at least formally speaking, still images, their impact is by no means static, since they derive their power to communicate from cultural codes, symbolic systems, and structures of desire that extend far beyond the paper on which they were originally printed and beyond the institutions of the cinema alone. For that reason, this website doesn’t limit itself to materials produced specifically for the promotion of kaijū eiga, but draws on the broader realms of film production and visual culture with which that genre interacted, and whose landscape it changed.

Film monsters feast on the visual. Since the monstrous denizens of celluloid don’t correspond to actual objects or beings in nature (and for that we surely should be grateful), they are visible yet intangible, significant yet insubstantial, real yet unreal. It’s only in the form of visual representations, and in the fantasies of those who conjure up or contemplate them, that they can be said to exist at all. In a sense, to analyze the nature of monster images is to tap at the heart of what monsters are and do. They “show” us things, as is reflected in the Latin word monstrum, from which the English word monster derives, and which is related also to such terms as to “demonstrate.” Although the Japanese expression kaijū has different linguistic roots, the potential for revealing something valuable through visual images is no less significant.

It’s been just over a decade since I acquired an interest in the visual codes that govern the world of kaijū, or to put it more grandiosely, the as-yet-unrecognized discipline of kaijū iconography. My interest in the visual puts me in the company of a growing number of historians who’ve begun venturing outside the limited domain of written documents, the traditional resource of our field, to explore the potential of other kinds of material from the past as a means of learning and of teaching. It’s not only scholars, of course, who’ve gotten visual of late. The students in my undergraduate classrooms, too, clearly respond more readily to images than to words alone. Perhaps it’s because they grew up in the visually saturated environment brought into being by the technological changes of the late twentieth century—the same environment in which made-in-Japan monsters from Godzilla to Pokémon germinated and thrived. The vicissitudes of mass culture have a real impact on the way we understand the world, producing not only fresh objects of research but also new modes of knowledge and tools for education.

The specific origins of this website project date to the period of a year or two before the fiftieth anniversary of the first Godzilla movie, which took place in 2004. As faculty director, at the time, of one of Columbia’s component institutions, the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture, I decided, with the help of colleagues, to organize an exhibition that would teach something about the place of Godzilla and his friends and foes in the history of twentieth-century culture. The resulting multimedia exhibit, “Godzilla Conquers the Globe: Japanese Movie Monsters in International Film Art,” took place in Columbia’s C. V. Starr East Asian Library from February through December 2004. I will never forget—and at least one librarian never quite forgave—the arresting sight of a garish array of giant vintage posters from France, Italy, and the U.S. staring down at the patrons of the main reading room, where dusty portraits of law professors and other more dignified souls once hung. Since that time, parts of the exhibit have traveled to other places, including Trinity College, Wellesley College, and the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas. I’m grateful to the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University for having provided the financial support that made it possible to stage the original exhibition. I also thank the Weatherhead Institute for its help in advancing this project to the next phase, which is the construction of this website. Any errors contained here are my own responsibility, and I encourage visitors to bring them to my attention after consulting the directions on the contact page.